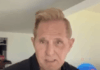

Inez Bordeaux, who was once incarcerated in St Louis’s Medium Security Institution known as the workhouse, is an organizer fighting for the facility to be closed. Photograph: Sid Hastings for the Guardian

A campaign called #closetheworkhouse describes ‘unspeakably hellish conditions’, but officials defend it as a ‘kind-of rescue’

Inez Bordeaux was at times left broke, homeless, and living in a halfway house over the years of unpleasant interactions with the criminal justice system in St Louis, Missouri. But the only time she ever felt hopeless was during the month she was incarcerated in the city’s infamous “workhouse” jail in 2016.

“I might not come out on the other side of this,” Bordeaux recalled thinking to herself. Her first three days were spent in solitary confinement after staff witnessed her crying, and deemed her a suicide risk.

“They took all my clothes and gave me a suicide smock, I couldn’t call anyone, talk to anyone, or read anything,” Bordeaux said.

A registered nurse and mother of four, Bordeaux was being held in the workhouse on a technical probation violation. Like 98% of inmates there, she was legally innocent but Bordeaux was being detained pre-trial because she couldn’t afford her $25,000 bail.

She describes the rest of her month in the workhouse as full of black mold, rats and blocked toilets churning up fetid waste. She was denied any outdoors time and basic feminine hygiene products.

“I say all the time that the workhouse is a hopeless place,” Bordeaux said. “When you first walk in you can feel the hopelessness. You can feel the desperation.”

Bordeaux was lucky to get out after just a month: the average stay in the St Louis workhouse is more than 190 days.

Today, Bordeaux is part of a growing movement of organizers, lawyers and those formerly incarcerated at the workhouse calling for the building, formally known as Medium Security Institution, to be shuttered.

Earlier this month, the campaign #closetheworkhouse released a report demanding its closure, and calling the workhouse a site of “unspeakably hellish conditions” and an extension of a racist criminal justice system.

Of those incarcerated in the St Louis workhouse, 90% are black, despite the fact that less than 50% of the city is black.

The report follows a class action file by the not-for-profit civil rights law firm ArchCity Defenders in November alleging that the site routinely violates the constitutional rights of inmates.

“This report highlights the systemic disparities and structural racism which have plagued our region for decades,” said ACD’s executive director, Blake Strode. “The workhouse in many ways symbolizes these destructive forces.”

‘I feel like a slave’

The day-to-day operation of the workhouse falls under the control of the city’s public safety director, Jimmie Edwards, who said that such graphic depictions of workhouse conditions are overblown.

“The only reason the narrative about conditions in the workhouse persists is because people refuse to visit and see for themselves,” Edwards said, offering the Guardian a walk-through of the jail.

Once inside, Commissioner Dale Glass, Superintendent Jeffery Carson, and Tonya Harry, chief of security, led a half-hour tour of the workhouse. That day, about 575 people were being held inside. The first inmate to speak out said to a guard, “What’s going on? I haven’t changed these clothes in two weeks.” A nearby guard came to address him as we watched.

Down the hallway, people inside called to get our attention. “Hey! We need to shut this place down right now.” Another said, “I feel like a slave inside here.” As we turned the corner we heard, “I’ve been here months, man, just waiting for a trial.”

Glass ascribed the remarks to inmate theatrics. “We’ve had a lot of tours here recently,” he said, “so forgive me that some of the inmates want to entertain.”

The tour came about a year after a regional heatwave turned attention to the conditions of prisoners in the facility, which did not have air conditioning. In July, more than 150 protesters gathered outside the workhouse, where temperatures inside reportedly exceeded 120F (49C), only to be dispersed by pepper spray. Three days after the protest, Mayor Lyda Krewson moved to place temporary air conditioning units in the facility.

The building is old, the air circulation is poor, but signs of infestation and mold were not apparent within the guided tour. The Guardian was not permitted to sit down with detainees or enter areas where detainees were actually held, however.

Sima Atri, a staff attorney with ArchCity Defenders, said numerous inmates had told her that they were told to clean so as to make the best impression for outside visitors. “And they all said they feared retaliation for speaking with us,” Atri said.

‘This place has been a kind-of rescue’

Organizers’ problem with the workhouse goes far beyond the the “hellish conditions” and deeper into the way the city uses incarceration – frequently as an answer to minor technical and fine-related violations.

The #closetheworkhouse campaign minces no words and calls the facility a debtors’ prison, noting that most inmates are presumed innocent and would be free to leave but for unaffordable bail amounts. The median bail in St Louis is $25,000, roughly the same as the city’s per-capita annual income – simply out of reach for most.

The organizers’ concerns run parallel with a broader movement in the US to end money-based bail practices, and likening pre-trial detention in jails to modern-day debtors’ prisons.

Back at the workhouse, even Glass and Edwards agree that too many people are incarcerated and that the bail system needs to be reformed.

But still, city officials try to spin the poverty angle back to their side in defense of the workhouse. “Honestly, this place has been a kind-of rescue for many people,” said Harry. Where else can you get three meals, healthcare, dental, AC in the summer, heating in the winter? We give some of these people structure.”

“We don’t have an old school Rikers situation on our hands here,” Edwards said, referencing the notorious New York City jail complex which has been the target of dozens of lawsuits alleging brutality and inhumane conditions.

“I think myself and Director Edwards have different definitions of what brings about community wellness and therefore public safety,” said Michelle Higgins, a lead organizer in the #closetheworkhouse campaign. “There’s a difference, you know, between an abolitionist and a reformist.”

In the last five years there have been six documented deaths at the workhouse. Edwards maintains that blaming the city is “unfair”, and said, “More often than not, they have nothing to do with the [workhouse], its conditions, or its employees.”

A glitch in the system

Bordeaux told the Guardian she never met Commissioner Glass or Superintendent Carson during her stay, and the argument that it’s a kind of safety net for people left her flummoxed.

“I don’t know how they can say that with a straight face,” Bordeaux said. “It’s easy to say those things when you can come and go on your own volition. But what happens when you come in without the suit and tie and stay the night?”

Her story of how she wound up in the workhouse is typical. In 2011 Bordeaux was pulled over, as black drivers in Missouri frequently are, and informed that there was a warrant out for her arrest for a larceny. She was miffed: “I had no idea what I had stolen.”

Prosecutors later informed her that the charges stemmed from an overpayment of unemployment benefits. If she went to court and lost, Bordeaux might not only have been looking at prison time, she would have lost her job too. “I couldn’t still be a nurse and have a felony charge,” Bordeaux said, so she took a plea agreement for probation.

In 2012, a glitch in the system assigned Bordeaux a new probation officer who no longer worked at the agency. When she was pulled over again in 2016, she was arrested for a probation violation because she never reported to an officer – who was not available to report to in the first place.

Bordeaux, who had lost her nursing credentials for a year, is back working with patients but still reflects on all that the system and the workhouse have cost her. “The time with my kids, the educational opportunities, the jobs, the money.”

Today, she spends much of her free time committed to closing the workhouse. “Every time I get the microphone, I’m calling out all elected officials in the city: get on the right side of this issue or get voted out in 2020. It’s that simple.”

Source: https://www.theguardian.com

Disclaimer: We at Prepare for Change (PFC) bring you information that is not offered by the mainstream news, and therefore may seem controversial. The opinions, views, statements, and/or information we present are not necessarily promoted, endorsed, espoused, or agreed to by Prepare for Change, its leadership Council, members, those who work with PFC, or those who read its content. However, they are hopefully provocative. Please use discernment! Use logical thinking, your own intuition and your own connection with Source, Spirit and Natural Laws to help you determine what is true and what is not. By sharing information and seeding dialogue, it is our goal to raise consciousness and awareness of higher truths to free us from enslavement of the matrix in this material realm.

EN

EN FR

FR

I would definitely like a petition to sign. That hateful place has NO BUSINESS operating to torture women’s spirits in any way. It must be closed. Those running it should be charged and placed in jail themselves.