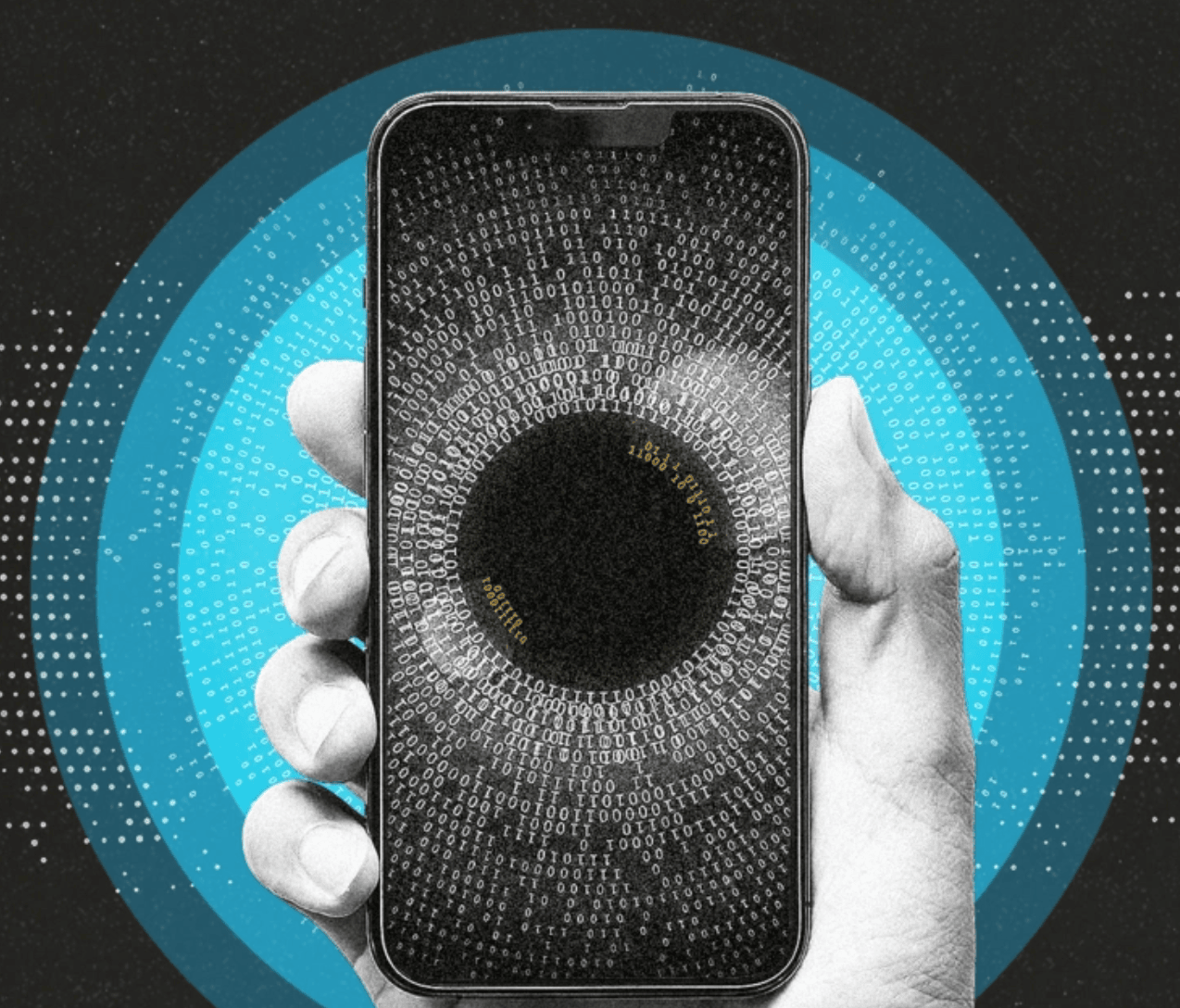

Consumer data has become a lucrative commodity, and the US government is buying.

The freakout moment that set journalist Byron Tau on a five-year quest to expose the sprawling U.S. data surveillance state occurred over a “wine-soaked dinner” back in 2018 with a source he cannot name.

The tipster told Tau the government was buying up reams of consumer data — information scraped from cellphones, social media profiles, internet ad exchanges and other open sources — and deploying it for often-clandestine purposes like law enforcement and national security in the U.S. and abroad. The places you go, the websites you visit, the opinions you post — all collected and legally sold to federal agencies.

In his new book, Means of Control , Tau details everything he’s learned since that dinner: An opaque network of government contractors is peddling troves of data, a legal but shadowy use of American citizens’ information that troubles even some of the officials involved. And attempts by Congress to pass privacy protections fit for the digital era have largely stalled, though reforms to a major surveillance program are now being debated.

On today’s episode of POLITICO Tech, Tau and I discussed the state of our personal privacy and the checks on all this government surveillance. I asked what differentiates the U.S. from authoritarian states like China when it comes to data collection, how our digital footprints will impact policy areas like abortion and what broader implications we can expect for civil liberties. He didn’t sugarcoat his responses.

“Any nightmare use for data you can think of will probably eventually happen,” Tau said. “It might not happen immediately, but it’ll happen eventually.”

The following interview has been edited down for length and clarity. Listen to the longer interview with Tau on today’s episode of POLITICO Tech, available on Apple, Spotify and Simplecast.

Tell me about this dinner. Why did it leave you so freaked out that you had to write a whole book?

This source described essentially a world in which the government had figured out that it could buy the geolocation data of cellphones, millions, possibly even billions of cellphones, mostly collected through apps or online advertisers, and it could use it in a surveillance program. And that’s what the Pentagon was experimenting with. It would eventually stand up and become a full-fledged program within the DOD. It would also expand to other government agencies like DHS. And it was a peek into a whole new way of doing surveillance that I hadn’t thought about.

The data that you’re talking about in this book, a lot of times it’s not data that’s collected through traditional legal channels or even through cyberattacks, but rather the government purchasing it from companies that have scraped it from mobile phones, ad exchanges, social media. What difference has that made in terms of both what the government knows about people and also how it uses that information?

A lot of these companies that I profiled in the book are virtually unknown to the average American. I think everyone knows what Google has about them. I think everyone knows what Facebook does. But these are companies, tiny, obscure data brokers, in some cases massive billion-dollar companies, but very little public-facing presence and almost no direct consumer relationship. Some of these companies focus on consumer data. Some focus on social data. Some focus on movement data.

Companies often claim that this data is collected with your consent and that it’s completely anonymous. But is that true?

When you dig deep into those claims, you’ll realize that neither is really true. That, for the most part, yes, perhaps there is some clause in a privacy policy that says that location data may be resold to other entities, but generally speaking, those privacy policies indicate that it will be sold for commercial purposes or for targeted advertising. Rarely, if ever, do they mention that there might be a government buying it; there might be some public safety entity or military unit using this data.

So the second main claim that a lot of these vendors make is that the data is anonymized, that they’ve stripped it of names or addresses that could reveal who a phone belongs to, say, in a geographical movement set. And that isn’t true either, because where your phone spends its evenings, for example, is likely the address of its owner, and it can be cross-checked against other property records. And in many other kinds of data sets, there’s ample evidence that you can be re-identified even if your name is not in them.

How much tension did you find there is within the government when it comes to the accessibility and use of this data?

I don’t want to give the impression that these government programs are poorly run or are violating the civil rights and civil liberties of Americans day to day. That isn’t the case that I found in my reporting. However, it’s certainly true that there is this tension between the United States being a society that’s privacy-oriented, that’s skeptical of the government, and the public safety and national security missions of all these government agencies. Lawyers and program managers and elected officials have to try to balance the fact that this data is out there. It’s available for purchase. It’s something that Home Depot can use to target ads. And the question that gets asked over and over again inside government is, if Home Depot can use it to target ads, why can’t we use it for our very important national security or public safety mission?

What exactly does the government do with this data?

The data is used in a wide variety of law enforcement, public safety, military and intelligence missions, depending on which agency is doing the acquiring. We’ve seen it used for everything from rounding up undocumented immigrants or detecting border tunnels. We’ve also seen data used for man hunting or identifying specific people in the vicinity of crimes or known criminal activity. And generally speaking, it’s often used to identify patterns. It’s often used to look for outliers or things that don’t belong. So say you have a military facility, you could look for devices that appear suspicious that are lingering near that facility.

Is there an example of what this leads to in the real world?

I’d point to the example of an Arizona man who was arrested because law enforcement saw that there were phones moving between a restaurant he owned on the U.S. side of the U.S.-Mexico border and Mexico. They figured out that there was a tunnel there and found a pretense to search his car and found drugs. [They] later got a search warrant to search his restaurant. So, we’ve seen it used in a wide variety of areas, including in situations where the government would otherwise need a warrant or some other sort of court order to get data on American citizens.

You compare to some degree the state of surveillance in China versus the U.S. You write that China wants its citizens to know that they’re being tracked, whereas in the U.S., “the success lies in the secrecy.” What did you mean by that?

That was a line that came in an email from a police officer in the United States who got access to a geolocation tool that allowed him to look at the movement of phones. And he was essentially talking about how great this tool was because it wasn’t widely, publicly known. The police could buy up your geolocation movements and look at them without a warrant. And so he was essentially saying that the success lies in the secrecy, that if people were to know that this was what the police department was doing, they would ditch their phones or they would not download certain apps.

That is the main theme of what I saw in looking at these government programs in the United States: That, by and large, the lawyers justified them on the grounds that they were open source, that this was data you could buy. But if you started poking around asking about them, FOIA-ing the contracts, they really didn’t want to talk about them.

You write in the book about what you call “gray data,” which is information that’s generated by this widening world of connected devices. How is that changing the nature of surveillance and this data that the government and others have access to?

So what I call gray data is essentially data that’s sort of there for the taking; that’s the byproduct of moving around the web or using some sort of service. So think of these Bluetooth devices that we all increasingly carry now. Your Bluetooth wireless headphones are actually just constantly pinging everything around it trying to tell a phone, another endpoint, that it’s there. And these clever governments or their contractors or these private companies have figured out, “Hey, you know, I could just run a little bit of code on a million phones around the world and just start vacuuming up all the Bluetooth signals around it.” And some of these contractors have found willing government buyers for this data.

Another example I give in the book is car tires. For example, did you know that your car tires actually broadcast a wireless signal to the central computer of your car, telling it what the tire pressure is? Well, that’s all well and good, and it’s there for perfectly legitimate safety reasons. But of course, governments have figured this out. They figured out that the car tire is a proxy for the car. And if you just put little sensors somewhere or you run the right code on devices that you scatter around the world, then you can kind of track people with car tires. I am familiar with governments experimenting with it. And there is a company that has put up sensors in various American cities that they claim is for traffic monitoring, and I think that’s probably correct. But I’m also aware that, at the very least, the intelligence community has figured out how to do it for national security purposes, too. I don’t know how deeply it’s penetrated to being a mass surveillance kind of technology, but it’s definitely something governments know how to use.

I wonder if you might connect some of these bigger questions about surveillance and about civil liberties to the ways it can affect everyday lives. One example that comes up in the book was abortion access.

With abortion access, you think about the fact now that there’s a patchwork of state laws around abortion and that in the previous era, before the Roe v. Wade decision, that was the reality as well. And in some states, there were these underground abortion clinics where people could go and have the procedure, even though it was against state law. And if you imagine trying to set up something like that today, I just don’t think it would be possible, and it wouldn’t be possible because all the devices we carry around, everywhere we go on an app like Uber, every email or Google query that we make or send is logged somewhere. The fact is that if a prosecutor in a state where abortion is illegal wants access to that data, they will get it. And so, essentially, we’ve built a society where everything is logged and when everything is logged, it’s very hard to move around the world with any sort of privacy or anonymity.

From politico.com

Disclaimer: We at Prepare for Change (PFC) bring you information that is not offered by the mainstream news, and therefore may seem controversial. The opinions, views, statements, and/or information we present are not necessarily promoted, endorsed, espoused, or agreed to by Prepare for Change, its leadership Council, members, those who work with PFC, or those who read its content. However, they are hopefully provocative. Please use discernment! Use logical thinking, your own intuition and your own connection with Source, Spirit and Natural Laws to help you determine what is true and what is not. By sharing information and seeding dialogue, it is our goal to raise consciousness and awareness of higher truths to free us from enslavement of the matrix in this material realm.

EN

EN FR

FR