Care homes under pressure to issue Do Not Resuscitate forms. Signatures forged on vital paperwork. And helpless families kept in the dark about their loved ones’ final hours…

Little about the 4.11am phone call from the care home seemed to add up. Gillian Grant was told her grandmother had deteriorated in the last few hours but that no ambulance had been called.

When she asked staff to do so, she was told: ‘I think it is beyond that stage.’

Assurances had been given days earlier that help ‘absolutely’ would be summoned if her condition worsened.

Ms Grant rushed to the care home, arriving just 19 minutes later yet, apparently, still too late. Staff greeted her with the news her grandmother had died ten minutes before. She asked to see her and, after being given PPE, was led through to her room.

‘Her mouth and her eyes were wide open,’ she recalled. ‘I tried to shut her mouth but it was too hard and I think rigor mortis had set in. She was stone cold and, in my opinion, she had been dead a lot longer than 20 minutes.’

It occurred to her the 91-year-old had succumbed to coronavirus in the Dunbartonshire care home some time before that phone call was placed.

But a young female member of staff assured her she had sat with the pensioner all night. Which made Ms Grant wonder: ‘If you have been sitting with my grandmother all night, why was I just called 20 minutes ago?’

Of the three members of staff on duty that night, one was a man in a dirty white T-shirt and jogging bottoms. He wore no PPE. Ms Grant was horrified.

Hours later she called the Care Inspectorate about what she had seen at Mavisbank care home in Bishopbriggs. She said: ‘I immediately panicked about the whole situation because I thought everybody is going to die here.’

But there was a still more shocking sight to come. It was a piece of paper known as a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) form for her grandmother – and Ms Grant’s name was on it as the next of kin authorising it.

Not only did she never authorise such a thing, but she had made it plain she had no intention of doing so. And yet, as a family member with power of attorney for her grandmother’s affairs, here was her name on a document which effectively denied a beloved relative potentially lifesaving treatment.Ms Grant has related the tale of her grandmother’s final weeks to the Scottish Covid-19 Inquiry which names the use of DNRs as one of its primary areas of investigation.

What the inquiry should find is the administration of this end-of-life procedure remained unaltered by the pandemic. The Scottish Government has, after all, repeatedly insisted there was no change to advice issued to clinicians about the use of DNRs – or DNACPRs (Do Not Attempt Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation) as they are also known.

But the evidence has deviated so far from this guidance that the prospect of criminal proceedings has now been raised. If a DNR form was forged, lawyer Aamer Anwar told the Mail, he would expect nothing less.

Was the DNR relating to Ms Grant’s grandmother then a one-off? Or was the manner of the death of the pensioner – who cannot be named due to reporting restrictions issued by the inquiry – indicative of a pattern?

Days ago, the inquiry heard from Madeana Laing, a manager at Beech Manor Care Home in Blairgowrie, Perthshire. She described a culture in which health professionals urged care homes to update their ‘anticipatory care plans’ for residents. She said she was told: ‘You need to look at who doesn’t have DNRs because they will now need to have one.’

Her response was that this was a discussion for GPs to have with family members – and yet within a couple of days, all the outstanding DNRs were in place. She questioned the extent to which family members were involved in these decisions. The clear impression, she said, was if a resident became ill from Covid – or even an unrelated illness – they would not be going to hospital.

She said: ‘You could clearly see that, if they went to hospital, they had a really good chance of improving, of getting over what was making them unwell in the first place. But it was almost like, you were not playing God, but it was just ‘no, you can’t go, so you just have to stay’.’

Her understanding, she said, was the DNRs were in place because of difficulties accessing ambulances, paramedics or hospital beds.

In the same day’s evidence, Peter McCormick, managing director of Randolph Hill Nursing Homes, said he believed NHS Scotland had taken a decision – one not discussed in public – that restrictions would be placed on people in care homes receiving hospital treatment.

He said in the case of one nursing home, DNRs were issued on a ‘blanket’ basis – as he understood it, because of the pressures on the NHS.

He said: ‘That couldn’t have been a nuanced discussion. There would have been no discussion involved in that.’

Another witness, Tressa Burke of Glasgow Disability Alliance, told of GP surgeries calling her members out of the blue and urging them to sign DNRs. She said it made them feel they were ‘not worth saving’.

In contrast to the experience in some care homes, others did refer patients with Covid to hospitals.

It happened to John Cowan from Ayrshire, who had moved into Windyhall Care Home in Ayr not through any infirmity of his own but because Annie, his wife of almost 60 years, needed to be there and the two were inseparable.

Within a few weeks he tested positive and an ambulance was called to take him to Ayr Hospital despite his symptoms appearing relatively mild. A few days later Mr Cowan was dead.

A DNR order was in place which his daughter Melanie, who had power of attorney for both her parents, knew nothing about.

That was why he was never transferred to an intensive care ward. Ms Hunter said she learned about the DNR from a nurse four days after her father was admitted.

She told the Mail: ‘She said she’d get the consultant to phone me, but he never did. He got one of the doctors below him to phone me.

‘From that conversation, I received very little reasoning as to why this had been done but he did agree it should have been discussed with me.

‘It was decided without my consent that my dad’s life wasn’t eligible for saving. In their eyes, my dad was dispensable. All they saw was an 83-year-old man who came from a care home. Not a husband who moved into the care home just to be with his wife.’

She added: ‘The Government allowed this practice.’

In her witness statement, Ms Hunter said that, a few hours before her father died, a male nurse ordered her to ‘stop asking them to help my dad as they were dealing with a very sick patient’.

She told of a nursing assistant her father had been ‘joking and laughing’ with when he was first admitted. After a week’s holiday, the medic returned to see how he was.

Ms Hunter said: ‘She said she couldn’t believe it. She had to come along and see him with her own eyes. It just didn’t make sense. She was standing in total shock and disbelief.

‘I got a strong look and feeling from her that something wasn’t right.’

It was, she said, a ‘horrific death’ in which her father ‘fought, struggled and thrashed around for 13 hours.’

The agony was compounded by the fact that, by then, Mr Cowan’s wife, who suffered from dementia, was in the same Covid unit. She was taken to see him on November 8, hours before he died and the sight of him left her bewildered. ‘She didn’t understand what was happening,’ said Ms Hunter.

Her mother was discharged after four weeks and returned to the care home, but it later emerged there was a DNR form for her too. Again, Ms Hunter knew nothing about it. Mrs Cowan died last December.

Evidence has also been heard in the inquiry from former senior nurse Margaret Waterton, 66, who lost both her mother and her husband to Covid in the space of a few months.

Both tragedies raise disturbing questions about DNRs.

When Mrs Waterton’s mother, Margaret Simpson, 86, was admitted to University Hospital Wishaw in Lanarkshire in May 2020 for an asthma-related illness, she tested negative for Covid on arrival.

But in the four nights she spent there, she was in four different clinical areas. Even pre-pandemic, Mrs Waterton said, such a level of movement of an elderly patient would be an infection risk. It is now clear her mother contracted Covid during that hospital stay.

On the day Mrs Simpson arrived home again, her daughter found an envelope in her hospital bags. Inside was a DNR form.

‘Mum had attempted to sign it the day she was admitted to hospital. I asked Mum if she knew what it was, and she said she didn’t. When I explained what it was and what it meant, she was horrified.

‘She didn’t recall signing it at that point but later, when she had time to think, she remembered that, when she was admitted to A&E, a doctor had spoken to her, but she didn’t understand what the doctor was saying and said that she felt the doctor was putting words into her mouth.’

An 86-year-old woman, whose medical notes say she was in a state of delirium on her admission, was, then, asked to sign a DNR on the spot.

Mrs Waterton took it up with the hospital and said the response from the medical director was ‘less than satisfactory’.

A few days later, Mrs Simpson was back in hospital, this time testing positive for Covid and gravely ill. Now, after a compassionate and reasoned discussion with a consultant, Mrs Waterton agreed with the assessment that her mother would be unable to withstand active resuscitation.

She was with her when she died on June 18, 2020.

Six months later, she and her husband of nine years David, 71, both tested positive and, a few days after Christmas, his condition worsened so severely she had to call 999 late at night for an ambulance.

The next morning she spoke to a doctor treating him at University Hospital Hairmyres in Lanarkshire and the news sounded ‘relatively positive’.

Mrs Waterton said: ‘I made it explicitly clear that I wanted David to be afforded every effort and every level of treatment made available to him.’

At the time, he was well enough to text and call her and there was no mention of DNR discussions having taken place.

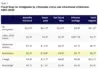

Each of these awful tragedies raise disturbing questions about DNRs [Stock image]

Besides, she said: ‘From previous conversations with David, I was clear that he would not agree to this and would want every effort and every level of treatment afforded him, including ventilation and ITU [Intensive Therapy Unit] care.’

Around New Year there was a disturbing phone call with a hospital consultant who wanted to know how far her husband could walk and how long it took him.

‘He kept pressing me about this specifically,’ said Mrs Waterton. ‘I recall feeling badgered by him and anxious about how my response would be used in the decision making.’

She told the Mail she did not want to answer his question. ‘I had this absolute sense this was going to drive something and I didn’t know what.’

She now strongly suspects it drove a DNR decision.

When her husband’s condition worsened, she was shattered to be told that he would not be moved to ITU, that he had received the ‘maximum treatment’ – and further, that all this had been discussed with her.

She remembers calling the nurse who told her this ‘a liar’. None of it had been discussed with her.

When she was finally allowed to see her husband on January 2, his first words were: ‘I thought I would never see you again.’

She said that, on seeing her and his daughter for the last time, ‘it was as if a wave of peace washed over him’. He died around 40 minutes later.

Mrs Waterton, a member of the Scottish Covid Bereaved group which is represented by solicitor Mr Anwar, said she was in no doubt about the tremendous efforts of NHS staff faced with unprecedented numbers of critically ill people.

But she said the ‘lived experiences’ of members and evidence heard at the inquiry suggested ‘bundles of DNACPR forms being posted through the letterboxes of care homes’ and consent for them being obtained ‘inappropriately’ in hospitals and used to determine further treatment.

Poor communication, she said, was a ‘consistent theme’ and, taken as a whole, it pointed to a ‘gap between the rhetoric and the reality’.

She said: ‘This has left us with not only many unanswered questions but also feelings of doubt about the decisions that were made and feelings of guilt that we could have and should have done more for our loved ones.’

M R Anwar said his understanding was any allegations of criminality, including forgeries of DNR documents, would be looked at by the Crown Office. He said: ‘The allegations made against certain care homes on the overwhelming use of DNR could only be described as a cynical practice, treating old people as expendable, toxic waste that they could discard.

‘These are very serious allegations which must be the basis of any criminal investigation into care homes.

‘The treatment of families was callous and cruel at the very moment they should have been comforted that their loved ones were being dealt with compassion and respect.’

For now, the Scottish Covid-19 Inquiry continues its examination of some of Scotland’s darkest days. Considerations of criminality do not fall within its remit. But hearings of a very different nature may follow in its wake.

From dailymail.co.uk

Disclaimer: We at Prepare for Change (PFC) bring you information that is not offered by the mainstream news, and therefore may seem controversial. The opinions, views, statements, and/or information we present are not necessarily promoted, endorsed, espoused, or agreed to by Prepare for Change, its leadership Council, members, those who work with PFC, or those who read its content. However, they are hopefully provocative. Please use discernment! Use logical thinking, your own intuition and your own connection with Source, Spirit and Natural Laws to help you determine what is true and what is not. By sharing information and seeding dialogue, it is our goal to raise consciousness and awareness of higher truths to free us from enslavement of the matrix in this material realm.

EN

EN FR

FR