By Elaine Buxton

Introduction and Review of Part 1

Part I of this California Water Shortage series outlined and described newly implemented water restrictions for Californians, blamed by water authorities, politicians and mainstream media on 20 years of drought, climate change, and population growth demands. It focuses on the Los Angeles Basin as the second largest city in the US with over 10 million people. Whereas the media and politicians justify the curtailments of water rights on low reservoir levels, particularly at Lake Mead and Hoover Dam on the Colorado River, the total problem, as well as the resources and solutions, is far more complex. The consequences of water supply and demand decisions, both in the short-term and long term are dire and will affect how many people and animals actually survive. This is not future speculation; it is happening now.

Part 2 begins by identifying who controls and manages our water, represented by an interfacing and complex network of unelected officials and government bureaucrats in charge of protecting, importing, allocating, and delivering water essential for life and food production. Each western state has its own systems and governing boards that interact with the federal Department of Interior. California has a complex water management system that can make your head spin trying to comprehend who does what and how they interconnect. Secondly, water rights and a brief history of how they were obtained is examined, which is important to understand as we go forward. Mistakes and greed that are not recognized or accounted for are likely to be repeated. Certainly, climate engineering is a critical causal element in the current situation and must be part of any solution, but is beyond the scope of this documentation.

The Watermasters of California

Established in 1902, the US Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) has constructed more than 600 dams and reservoirs in 17 western states. It is the largest wholesaler of water and the second largest producer of hydroelectric power in the United States. Its mission is to assist in meeting the increasing demands of the West, protecting the environment, honor Native American Tribes’ water rights, and partner with the states in water delivery obligations. USBR has two regions that include California: California Great Basin Region 10 and Lower Colorado Basin Region 8.

Region 10 includes Shasta, Trinity, Klamath, Feather, Sacramento, and San Joaquin river watersheds and the Central Valley Project (CVP). Construction of major CVP projects began in 1938 for the Shasta Dam, then expanded into a system of 20 dams over the next 50 years, holding up to 12 million-acre feet (MAF)of water. Region 8 includes Lake Mead, Colorado Aqueduct, Salt River, and projects for Central Az, San Diego, and Yuma. The Commissioner is currently Camile Calimlim Touton, appointed by the Biden Administration. New agreements between the lower Colorado basin states began in 2021 and will continue to be implemented into 2023 due to drought conditions. CVP supplies water to 29 out of 58 counties in California, representing about 30 percent of the total supply. Water from Lake Mead represents 90 percent of the water supply for Las Vegas.

Two primary statewide agencies include the Dept. of Water Resources (DWR), and the State Water Resources Control Board. They each have extensive programs and responsibilities, along with local offices. Each basin also has a court appointed watermaster for regional oversight of ground water management and storage. Additionally, the LA Basins have four groundwater quality agencies and 7 sets of municipal water delivery. The Department of Public Works & Flood Control District is responsible for water conservation, reservoirs and surface water rights. The LA Department of Water and Power is another key player in the network with an extensive infrastructure. Each will be described briefly below.

The Department of Water Resources is one of seven state departments that fall under the umbrella of the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA). DWR has 11 main divisions, approximately 3,500 employees, 8 main offices, 5 field divisions, 4 regional offices and over 800 programs. The DWR manages the State Water Project (SWP), jointly operates the CVP, oversees the implementation of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), serves as the statewide flood control agency, and leads statewide water resource planning (Water Resilience Portfolio, 2019). It also has the following responsibilities:

- Preventing and responding to floods, droughts, and catastrophic events

- Informing and educating the public on water issues

- Developing scientific solutions

- Restoring habitats

- Planning for future needs, climate change impacts, and flood protection

- Constructing and maintaining facilities

- Generating power

- Ensuring public safety

- Providing recreational opportunities.

The executive director for the Dept of Water Resources is appointed by the governor and confirmed by the state senate. This position is currently held by Karla Nemeth. She was first appointed by Governor Brown in January 2018 and reappointed by Governor Newsom in June 2019. The full executive team biographies, organizational chart, affiliated boards and commissions can be found at www.water.ca.gov. CRNA and DWR produce a weekly California Drought Update, which can be found online at www.drought.ca.gov. The update report advises of any recent actions taken and upcoming events where local leaders discuss the water issues.

The State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) was created by the legislature in 1967 and given broad authority to protect water quality and balance competing demands on water resources. It is a regulatory board that allocates water rights, adjudicates rights disputes, develops statewide protection plans, establishes water quality standards, and guides its nine Regional Water Quality Boards located in major watersheds. The SWRCB Chair is E. Joaquin Esquivel, who was first appointed by Gov. Brown in 2017 and reappointed by Gov. Newsom in 2019. There are five full time members of the SWRCB, also appointed by the governor. All members must be qualified in the field of water supply and water rights plus one member must be an attorney, one member a civil engineer, one a professional sanitary engineer, and one member qualified in water quality. Each Regional Board consists of seven members and serves as frontline staff for state and federal water pollution control efforts.

Until this year’s curtailments, California agriculture produced almost half of US-grown fruits, nuts and vegetables. Water discharges from agricultural operations include irrigation runoff, flows from drains, and stormwater runoff. These discharges can affect water quality both on the surface and underground by transporting pollutants, such as pesticides, sediment, nutrients, salts, pathogens and metals from the surface. To prevent discharges from impairing water resources, the Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program (ILRP) of the SWRCB issues waste discharge requirement to growers (WDRs). Approximately 40,000 growers are enrolled in this program, covering 6 million acres. The SWRCB issues monthly status reports for the ILRP.

A Cannabis Cultivation General Order, policy and guidelines and small irrigation permits were approved in 2017 and updated in 2019 to prevent runoff discharges, which is a simple form of a WDR described above. This applies to both indoor and outdoor sites. No surface water can be diverted off the grower’s property during the dry season. Growers can store water ahead of time up to 6.6 acre-feet or obtain a permit for fully contained springs.

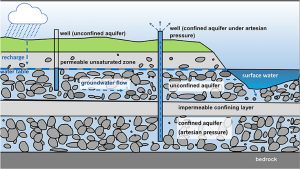

The SWRCB also regulates any seawater desalination facilities and vessel discharges along beaches. And in addition to meeting supply and demand with the continuing struggles over river flows and population growth, the SWRCB is responsible for fixing ailing sewer systems, building new wastewater treatment plants, and tackling underground pollution from industry. Its Groundwater Ambient Monitoring and Assessment Program (GAMA) is a comprehensive plan that integrates monitoring with the Regional Water Boards, the DWR, the Dept of Pesticides Regulations, the US Geological Survey, local water districts and well owners. This is important because 9 out of 10 public water systems rely on groundwater, at least partially.

There are four Groundwater Quality Agencies in the LA Basin as follows:

- Los Angeles County Flood Control District, which owns and operates 22 miles of seawater barrier facilities (West Coast Basin Seawater Barrier and Dominguez Gap Barrier). WRD purchases the water used for injection, now 50-75% recycled water.

- Water Replenishment District of Southern California (WRD)

- Upper Los Angeles River Area Watermaster (DWP)

- San Gabriel Basin Water Quality Authority. Established in 1933, it merges San Gabriel Valley MWD, Upper San Gabriel Valley MWD, and Three Valleys MWD.

Groundwater development grew dramatically with the introduction of deep well turbine pumps in 1909. However, demand exceeded natural replenishment, causing depletion of underground aquifers. Overdrafts caused the water levels to drop with risk of sea water intrusion. The deteriorating situation led to the formation by the Central Basin and West Coast Basin Associations of the Water Replenishment District of Southern California (WRD) in 1959 to manage, regulate and replenish the basins.

The basin Watermasters oversee groundwater pumping, recharge operations, pumpers legal water rights and storage. Every groundwater pumper must report its extractions to the Watermaster. Panels for water rights and storage issues meet regularly. The Watermasters publish annual groundwater reports, available to the public. The reports include groundwater levels, annual pumping rights, allocations to large agencies, and more. All water rights are legally binding agreements among pumpers and approved by the courts. Beginning in 2014, the SWRCB required utilities and municipal suppliers to report per capita consumption by residents using standardized methods for comparable data. Permits for placement of individual wells must be obtained from the LA County Dept of Health Services, the basin watermaster, and the Regional Water Resources Control Board.

The basin Watermasters oversee groundwater pumping, recharge operations, pumpers legal water rights and storage. Every groundwater pumper must report its extractions to the Watermaster. Panels for water rights and storage issues meet regularly. The Watermasters publish annual groundwater reports, available to the public. The reports include groundwater levels, annual pumping rights, allocations to large agencies, and more. All water rights are legally binding agreements among pumpers and approved by the courts. Beginning in 2014, the SWRCB required utilities and municipal suppliers to report per capita consumption by residents using standardized methods for comparable data. Permits for placement of individual wells must be obtained from the LA County Dept of Health Services, the basin watermaster, and the Regional Water Resources Control Board.

As described in Part 1 of this series, WRD is the largest groundwater agency by population in CA, serving 4 million residents and 43 cities over a 420 square mile region of LA County. In 2013, WRD was court appointed as the Watermaster Administrative Body for both the Central and West Coast Basins. WRD owns 2 advanced water treatment facilities and a groundwater desalter. It controls all groundwater pumping, water right sales and leases, storage and carry-over conversions for the LA region. WRD procures imported water and recycled water for the seawater barriers. It supplies about 20 percent of total retail demands in the basins. Stephan Tucker is the General Manager of WRD. Prior to this position, he worked on equity related programs for the LADWP for 20 years. He is a mechanical engineer with more than 34 years of water management projects.

As part of its flood control and water supply responsibilities, The Department of Public Works and Flood Control District operates and maintains 15 major dams, 27 spreading grounds, 483 miles of open channels, 47 pumping plants, 3 seawater intrusion barriers, 172 debris basins, and 27 sediment placement sites encompassing 2,700 square miles and 6 watersheds. The DPW is a major player regarding water resources for unincorporated areas. Five more dams are operated by DPW jointly with the US Army Corps of Engineers. The department was formed in 1985 as a merger for watershed management, building water systems, storm drainage and flood protection, recharging groundwater, providing recreation, and water conservation. DPW is governed, as a separate entity, by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors.

Within the Los Angeles basin, the Los Angeles Dept. of Water and Power (LADWP) was established in 1902 to deliver water to the City of LA. Electric distribution began in 1916. It is governed by a 5- member board of commissioners, appointed by the mayor, along with the General Manager. It has 10,000 employees and serves over 4 million residents. LADWP is also a board member of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California that provides water from the Colorado and California Aqueducts.

LADWP operates eight major active reservoirs and 110 smaller storage facilities, all of which provide operational flexibility to meet demand. There are over 80 reservoirs in the county and LADWP manages most of them. LADWP built and operates the Headworks East and West Reservoirs in Griffith Park described in Part 1 and is just one of many infrastructure investments. Active reservoirs now are trending to be protected with a roof or floating membrane to meet drinking water quality standards. Others are no longer in service but still contain water. Some smaller reservoirs are fed by larger reservoirs such as Lake Mead via a chain of tunnels or canals for additional storage. This explains why only considering the water level of Lake Mead hides the full storage capacity and water resources of the LA basin. LADWP’s Urban Water Management Plan includes expanding recycled water and stormwater captures for groundwater recharging for the future.

The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD) is a water wholesaler for municipal uses and has no retail customers. Its members are comprised of 14 cities, 11 municipal water districts and one county water authority. Its principal water sources are the SWP and the Colorado River. The SWP is owned by the state, is operated by the DWR, and delivers water via the Colorado River Aqueduct, which is owned and operated by MWD. LADWP is a member agency and relies on water from MWD not otherwise supplied by the Los Angeles Aqueduct, local groundwater and recycled water.

Parker Dam at Lake Havasu, downstream from Lake Mead, is the source of water for the Colorado River Aqueduct, operated by MWD, and remains at full at 98 percent capacity currently in 2022, although Lake Mead is at 34 percent capacity. MWD paid for nearly the full cost to build Parker Dam, although it is officially owned and run by USBR. Half of the hydroelectric power generated by Parker Dam is used by MWD to pump water along the Colorado River aqueduct. At the end of 2021, MWD had a record 8.2 MAF in storage. MFD has “banked” unused water for later use in drought years and water sales. MWD is the major driver for California’s proposed Delta Conveyance Project and Sites Reservoir, funding most of the engineering plans.

Water Rights

California’s system of state water rights has a profound effect on who gets how much water and when, particularly during times of drought. The water in California is considered to be the property of the people of the State, and anyone using the water must acquire the right to do so. CA recognizes both riparian and prior appropriation doctrines. Under riparian doctrines, a person who owns land bordering a watercourse has the right to make reasonable use of the water on that land, although this can be reduced during times of shortage. Under the prior appropriation doctrine, a person who diverts water from a watercourse and makes reasonable use of it, has a right to do so. Appropriated rights are filed in order of seniority with permits from the SWRBC.

Both the CVP and the SWP acquired rights for water use from the State of California between 1927 and 1967. Because the USBR took the water rights of other users to construct the CVP, it entered into settlement/exchange contracts with water users predating the CVP. The settlement contractors includes both individuals and water districts who receive 100% of their contracted amounts in most water year types, unlike other water service contractors. Their annual entitlement may not be reduced by more than 25% in critical years. All pumping rights by water districts are legally binding agreements approved by the courts and the watermasters. Twenty-two of the tribes along the Colorado River have senior rights, but the amount of water rights still remains unresolved for 13 more tribes. The tribes have only been using about half of their allocated amounts.

History of LA Aqueduct Development

From the mid 1800’s to mid-1900’s, the LA Basin suffered a series of catastrophic events including droughts, floods, fires, mudslides and earthquakes with significant loss of life. Sociologist Harvey Molotch wrote of LA, “The rise of this region can only be explained as a remarkable victory of human cunning over the so-called limits of nature.” (Water For LA County, History, www.waterforla.com)

Although LA only receives an average of 15 inches of rain per year, there have been horrendous downpours. In 1861 it rained heavily for 45 days straight with 66 inches, washing away whole towns, drowning cattle and ripping apart farms and land. That was followed by intense drought from 1862-1864, killing 70% of the cattle. Another three-week deluge left one-third of downtown LA underwater for hours in 1884, destroying bridges and homes. Flooding happened again in 1886. By then the LA County Board of Supervisors decided to take flood control action by hiring a team of engineers.

By 1910, in spite of an 11-year drought from 1893-1904, 500K people were living in LA County. Groundwater pumping had become possible but rapidly overdrew the water table. The region’s top water engineer, William Mulholland, famously said, “if you don’t get the water, you won’t need it.” It was Mulholland, along with his friend and former LA mayor Frederick Eaton, who turned to the Owens Valley in the Sierra foothills, 200 miles northeast of LA County, for water. They were instrumental in getting the funding, permits and 5,000 construction workers to build the 233-mile long Los Angeles Aqueduct between 1906-1913. That water allowed LA to grow into a giant metropolis at the expense of all agriculture in Owens Valley. Mulholland and his associates were criticized for using deceptive tactics to obtain Bureau of Reclamation rights to the Owens River and force farmers off the land.

By 1910, in spite of an 11-year drought from 1893-1904, 500K people were living in LA County. Groundwater pumping had become possible but rapidly overdrew the water table. The region’s top water engineer, William Mulholland, famously said, “if you don’t get the water, you won’t need it.” It was Mulholland, along with his friend and former LA mayor Frederick Eaton, who turned to the Owens Valley in the Sierra foothills, 200 miles northeast of LA County, for water. They were instrumental in getting the funding, permits and 5,000 construction workers to build the 233-mile long Los Angeles Aqueduct between 1906-1913. That water allowed LA to grow into a giant metropolis at the expense of all agriculture in Owens Valley. Mulholland and his associates were criticized for using deceptive tactics to obtain Bureau of Reclamation rights to the Owens River and force farmers off the land.

Then by the 1930’s, LA’s population growth demanded more water. LADWP bought water rights to the Mono Basin just north of Owens Valley and built an extension to the aqueduct, tunneling through an active volcanic field. Mono Lake, which had been a vital migratory bird refuge, was drained to the point it could not support wildlife. In 1979, the Mono Lake Committee and National Audubon Society sued LADWP, and the litigation reached the CA Supreme Court in 1983. Eventually, in 1994, the SWRCB ruled that the LADPW had to refill Mono Lake to at least 20 of the previous 25 ft level. As of July 2022, the Mono Lake level is 6,379 feet, or 12.5 feet below the management level (www.monolake.org).

Part 2 Summary: Is Shortage Natural, Artificial or Engineered?

Los Angeles County has a vast array of dams, reservoirs, aqueducts, pumping stations, treatment facilities, seawater barriers, injection wells, and spreading grounds, which are managed by a maze of agencies to meet supply and demand, water quality standards and flood control. Water resources include imported water, ground water, recycled water, desalinated water and locally stored water. All pumping and aquifer recharging is closely monitored. All water rights are legally binding and court approved.

Each region, basin and watershed of California has unique water supplies, environmental conditions, user needs, and vulnerabilities. This means that a one-size-fits-all approach to building water resilience doesn’t work well. Northern regions of California with more water have been required to share significant amounts with semi-arid coastal southern California cities and counties, sometimes devastating their own ecosystems and agriculture. Still, there is not enough to go around, making conservation and efficient uses of water critical. It takes a massive amount of planning, knowledge, foresight, and infrastructure to keep everything working and balanced in managing an urban area like LA with 10 million people who have little natural water resources. Collaboration between the water agencies, local, state and federal governments, industry, farmers and other stakeholders is crucial for good stewardship and equity. Everyone must have the opportunity to sit at the table.

The interlocking maze of water sellers and watermasters is complex which can be overwhelming, so there is little wonder that many people haven’t taken the time to comprehend it. The complexity also makes it burdensome for those working within the industry and regulatory bodies to collaborate and formulate lasting agreements. All of the information presented here is available online, although it does take determination to find it. What is clear, too, is that that mainstream media and the California governor have engaged in some fear mongering that LA is already on the verge of running out of water because of dropping levels in Lake Mead, as if it were the single source of water for California.

Politicians rarely reveal the storage of groundwater or the other 80+ surface reservoirs in the LA Basin to the public. Neglecting to fully inform the public is a form of political manipulation. On the other hand, the pubic also has a responsibility for seeking out information, readily available even on government documents for the price of one’s time. Yes, wise use of water is important, but LA is not going to run out of water or power for this year or next, even if the California drought continues.

To answer the question if the water shortage is natural, artificial or engineered, it has aspects of all three. The cause of the perceived water shortage in California is partly natural due to the semi-arid climate with repeated droughts over the last two centuries. The population growth could not have been sustained without imported water from other parts of the state. Water diversions to southern California supported population growth, agriculture with high water needs, golf courses and large estates with expansive lawns with little regard for agriculture, fishing rights or wildlife in northern parts of the state. River beds have been paved over with cement and forests have burned. Water rights, although legal, have not been equitable for all potential consumers who need water to thrive. All of this poor planning reflects artificially created problems. And although it is a controversial idea, climate control, the destruction of forests, and loss of farmland may be engineered for the depopulation Agendas 2021 and 2030 of the World Economic Forum for sustainable development. And unquestionably, limiting public access to water justified only by a single reservoir that is partially drained to fill reservoirs largely unknown to the public, represents an engineered control of a valuable resource.

Part 3 of this California Water Shortage series coming tomorrow will examine solutions for improved water management in the past, present and future. There are many options and alternative pathways to resolve the problems of each sector.

For more on the drought scandal, check out this recent video by Jimmy Dore: https://youtu.be/sAhJak7AiIY

Watch this interview with Elaine and Reinette Senum discuss the issue: https://reinettesenumsfoghornexpress.substack.com/p/citizen-sleuth-elaine-buxton-uncovers?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email#play

And PLEASE circulate this letter from Senator Hurtado who represents the 14th District in California’s Central Valley and contributed to the Clean Water Act. https://sd14.senate.ca.gov/sites/sd14.senate.ca.gov/files/pdf/CA%20Legislature-DOJ%20Water%20Market%20Manipulation%20Letter.pdf

Disclaimer: We at Prepare for Change (PFC) bring you information that is not offered by the mainstream news, and therefore may seem controversial. The opinions, views, statements, and/or information we present are not necessarily promoted, endorsed, espoused, or agreed to by Prepare for Change, its leadership Council, members, those who work with PFC, or those who read its content. However, they are hopefully provocative. Please use discernment! Use logical thinking, your own intuition and your own connection with Source, Spirit and Natural Laws to help you determine what is true and what is not. By sharing information and seeding dialogue, it is our goal to raise consciousness and awareness of higher truths to free us from enslavement of the matrix in this material realm.

EN

EN FR

FR