From contributor Elaine Buxton:

Causes, Determinants of Population Health, Pandemic, ED Boarding & Utilization

This is the second article in my health care series, describing the severe overcrowding of hospital emergency departments (EDs) in the US and its consequences that has been occurring for decades with few effective solutions. I recently spent three days boarded in an ED, and so have first- hand experience of the magnitude and chaos occurring there. ED’s are now the central hub of both inpatient and outpatient healthcare in ever-expanding roles. There are multiple reasons for overcrowding, including the decline of population health. The broken American health care system is in dire need of reforms and restoration to higher quality, effectiveness and equity.

Health care demands, systems and management have overtly changed since the COVID pandemic, with its lockdowns, mandatory masking, injections, protocols, financing, and censorship of clinical staff who differed from the Deep State narrative. See my post Perspectives About the American Health Care System for a review of what happened to the public health sector, shrinking of personal freedoms, and truth in science related to COVID -19.

Causes of Emergency Department Overcrowding

· Declining population health and social determinants of health (SDH)

· Pandemics (COVID-19)

· Slow processing and flow of ED patients, lack of efficiency, ED boarding

· Insufficient hospital inpatient capacity (beds or nursing staff)

· Insufficient number of ED beds or rooms, physicians/ advanced practice providers

· ED is primary gateway to most inpatient hospital services

· Increased complexity of diagnosis, procedures, technology available to urban EDs

· Insufficient access to primary care by patients

· Referrals by primary, specialists and community hospitals for diagnostics, assessments and treatment (including side effect management of chemotherapy)

· Insufficient access to mental health services and substance use treatment

· Growing frequency of drug overdoses

· Growing numbers of uninsured, Medicaid, and immigrant patients

· Aging population in certain regions

· Influx of migrants to urban areas

· Misuse by patients for non-urgent conditions (avoidable visits)

· Urban centers often are regional hubs for rural areas, with a need for expansion to meet the need beyond local population

· American emphasis on disease treatment rather than health and holistic wellness

· Decreased insurance and Medicare reimbursement to hospitals

· Hospital closures since 1985 resulting from reduced Medicare reimbursements.

· Misaligned health care economics for profit (ie Big Pharma)

· Politicization of public health care policies and science

There have been many agency and research attempts to identify ED visits that could be avoidable, or unnecessary, to decrease ED overcrowding over the past two to three decades, although little progress has been made. Prospectively, it is difficult to determine which patient presenting with acute chest pain is “avoidable” (e.g. acid reflux or gastritis) versus those with an emergency medical condition (e.g. acute coronary syndrome or cholecystitis).

One approach has been myriad yet unsuccessful pushes to “keep patients out of the ED” by expanding primary care access. This has resulted in only minor gains, because the ED still affords a unique opportunity for immediate, on-demand access to a full evaluation including laboratory testing and imaging that would otherwise be fragmented within the ambulatory care paradigm.

The root cause of ED crowding does not intrinsically reside in the emergency department, nor with individual patients. It’s the American health care system that is badly in need of an overhaul.

What is quality health care and population health?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “the state of complete physical, mental, and social well- being, and not the mere absence of disease or infirmity”. This well-being concept of health is multi-dimensional. Health care services for the sick and injured is just one component of achieving population good health and well-being. In order to have positive population health outcomes, sustaining a healthy natural environment, equitable social and economic policies and strategies, good governance, a competent and motivate health care workforce, adequate financing to enable quality care, available supply chains for supplies and equipment, up-to-date technology in facilities and information systems must be sustained by nation states. The responsibility for population health is shared by multiple sectors of any economy.

In contrast, the US health care systems emphasize treating disease and its symptoms, rather than prevention and wellness. Functional medicine and naturopathic medicine seek to treat root causes of illness, but is either not covered by health insurance or practiced by few allopathic doctors. Allopathic systems are profit driven, even among NGO’s and the pharmaceutical industry. Allopathic drugs replaced herbals, homeopathic medicines and vibrational energy treatments following the Flexner Report by 1920 when all American medical schools switched their educational programs to match it with funding from the Rockefeller and Carnegie Foundations. Drugs, surgery, radiation and physical therapy are the mainstays of allopathic care, but not preventive care. Allopathic medicine only endorses a narrow band of the WHO definition of health.

For example, many allopathic doctors advise their patients that vitamin supplements are ineffective and even risky. Few of them know anything about nutrition. They ignore the importance of supplying the body with adequate nutrients, such as minerals required for metabolic processing by the body. Although every doctor studies biology and physiology in medical school, they don’t seem to apply that preventive information in practice with their patients.

A relative of mine recently went to the ER for respiratory, flu-like symptoms for 4 days and a positive COVID home test. She was told that there is no early treatment for COVID and just to rest and drink fluids. Only return if the COVID progresses into the lungs, when treatment is much more difficult. Hospitals are still following Dr Fauci’s “no early treatment” advice! During my ED visit, I was also told by the nurses that the hospital protocol states there is no effective early treatment for COVID. They do not ever prescribe Ivermectin or vitamin supplements. I informed a hospitalist doctor of early treatment measures, and he responded by telling me that all those studies are misinformation and useless.

Measuring Population Health

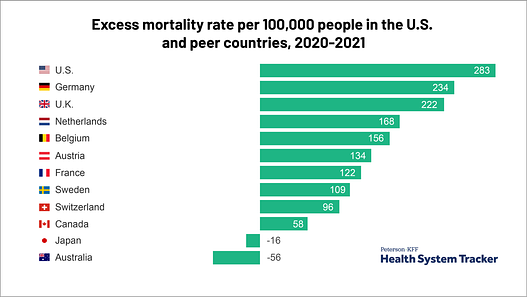

Population health decline is one reason hospital departments are overcrowded. It has been deteriorating in the US for at least three decades, and worsened during the COVID pandemic. Recall that Dr Fauci was responsible for public health policies and research during that time. The US spends nearly twice as much on health strategies as other developed nations but has the lowest average life expectancy, performs worse on many population health outcomes, and has more outcome-related disparities between income groups. More illness leads to more need for health care services.

Tracking of historical trends provides indicators of general population health status and identifies where interventions are needed. At the beginning of the 20th century, the US population was characterized by a low standard of living, poor hygiene, and poor nutrition. Communicable diseases in acute conditions were then major causes of most premature deaths. Public health measures such as improved sanitation and drinking water treatment led to a dramatic increase decrease in death due to infectious diseases and a marked increase in life expectancy.

Presently, chronic diseases such as heart disease and cancer have become the leading causes of death. These diseases require a different approach to prevention detection and treatment compared to the infectious and acute illnesses more common in the past. The causes of increasing cancer and heart disease rates in the US needs more examination.

A wide range of factors can be used to measure the health status of a population: Birth and death rates, life expectancy, quality of life, and morbidity from specific diseases and conditions are reported by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and WHO. The World Health Organization (WHO) calculates health statistics for its 194 member states.

· General mortality: the number of all deaths and leading causes of death. CDC reported the four leading causes of death in the US in 2022 as heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries, COVID. COVID ranked as # 3 in 2021.

· Infant mortality: number of infants who die before their first birthday. In 2019, WHO reported the US as 47th for low infant mortality rates among its members.

· Life expectancy: average number of years a newborn is expected to live if current death rates remain constant. In 2019, 39 member states of WHO reported longer life expectancies than in the US.

Health Determinants

Broader determinants of population health include environmental risk factors such as air and water quality, use and quality of ambulatory care and inpatient care, financial and geographical accessibility of health personnel and facilities, health insurance coverage, socio-economic status of communities and groups, behavioral and genetic risks, level of preventive care, and many other factors. These indicators represent cumulative effects of public health strategies and health care. Population health outcomes result from a complex web from cultural, environmental, political, social, economic, behavioral, and genetic factors. Generally, those with money, power and resources have more opportunities to achieve optimum health.

Specific environmental health determinant (EDH) categories include physical, chemical and biological factors. This could be further divided into built vs natural determinants. Built includes all buildings, spaces, products and conditions created by people. Specific examples include pandemics, mandated vaccines, Covid lockdowns, chemtrails, wildfires, geoengineering (extreme weather manipulation), multiple toxic chemical spills, any contamination of air, soil or water, GMO processed food, microplastic pollution, WIFI and 5G, domestic violence, clean drinking water scarcity, poor sanitation, household crowding, lack of open space, unaffordable housing, noise.

Adverse social determinants of health (SDH) include poverty, racial discrimination, neighborhood and police violence, domestic violence, unequal distribution of resources and education, lack of access to physical and mental health services, poor working conditions, lack of transportation, grocery stores without fresh produce, and few public spaces such as parks.

As an example of how social factors influence behavior, consider level of education. A person’s level of education and economic status directly influences their sense of health, understanding that lifestyle choices about food and exercise impact their lifespan, and unfortunately, opportunities for access to high quality care. The impact of dire socio-economic factors faced by millions of people every day cannot be ignored, partially shaped by education, occupation, income, cultural norms and communities they live in. All this add up to lots of STRESS. Stress directly causes changes in our physiology.

Individuals generally do not directly control ALL the determinants of their health because the social, economic and physical environment inequities are so significant, with the disadvantaged carrying the greatest burden of disease and injuries. Though that does not exclude the importance of self-responsibility for making good choices as much as possible.

Excess Mortality and Morbidity from COVID Pandemic and C-19 Injections

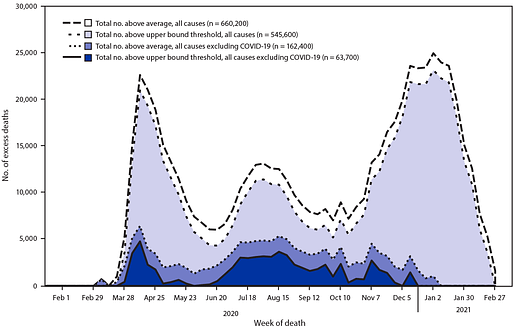

I want to make several observations about excess death reports. First, one of the after-effects of the COVID pandemic is that more people are sick and dying in the global West, which directly reflects the number of people seeking care from hospitals. Excess deaths have risen since COVID-19 arrived, as reported by multiple sources worldwide.

Excess deaths are typically defined as the difference between the observed numbers of deaths in specific time periods and expected numbers of deaths in the same time periods. Weekly counts by the CDC of deaths are compared with historical trends to determine whether the number of deaths is significantly higher than expected. Counts of deaths from ALL Causes, with and without COVID deaths are compared. Estimates of deaths can be calculated in various ways, depending on the methodology and assumptions made.

Second, many of us know that nearly every statistic on mortality and morbidity is manipulated in numerous ways. For example, PCR tests were used initially that counted influenza and colds as positive for C-19, but is now officially recognized as an unreliable method, particularly in light of the number of magnifications employed to detect genetic material. That is why there was essentially no influenza from 2020-2021. Hospitals however continue to use PCR tests (how I was tested, diagnosed and treated).

Third, hospitals were paid a bonus for each COVID diagnosis placed on the death certificate, even if patients died from totally unrelated causes, such as heart attacks, cancer, or trauma. Patients with a positive PCR were treated with toxic drugs such as remdesivir, sedated and placed on ventilators, then listed as dying from COVID. Morticians began reporting a dramatic increase in deaths by 2021, although autopsies were still banned. Elective surgeries were often cancelled and cancer patients could not get treatment. This means that the excess deaths were both directly and indirectly related to COVID via infection, vaccine adverse effects, lack of treatment for other conditions, and stress from lockdown effects on health.

Fourth, not all countries have the infrastructure and capacity to register and report all deaths. In richer countries with high-quality mortality reporting systems, nearly 100% of deaths are registered. But in many low- and middle-income countries, undercounting of mortality is a serious issue. The UN estimates that, in “normal” times, only two-thirds of countries register at least 90 % of all deaths that occur, and some countries register less than 50 % of deaths.

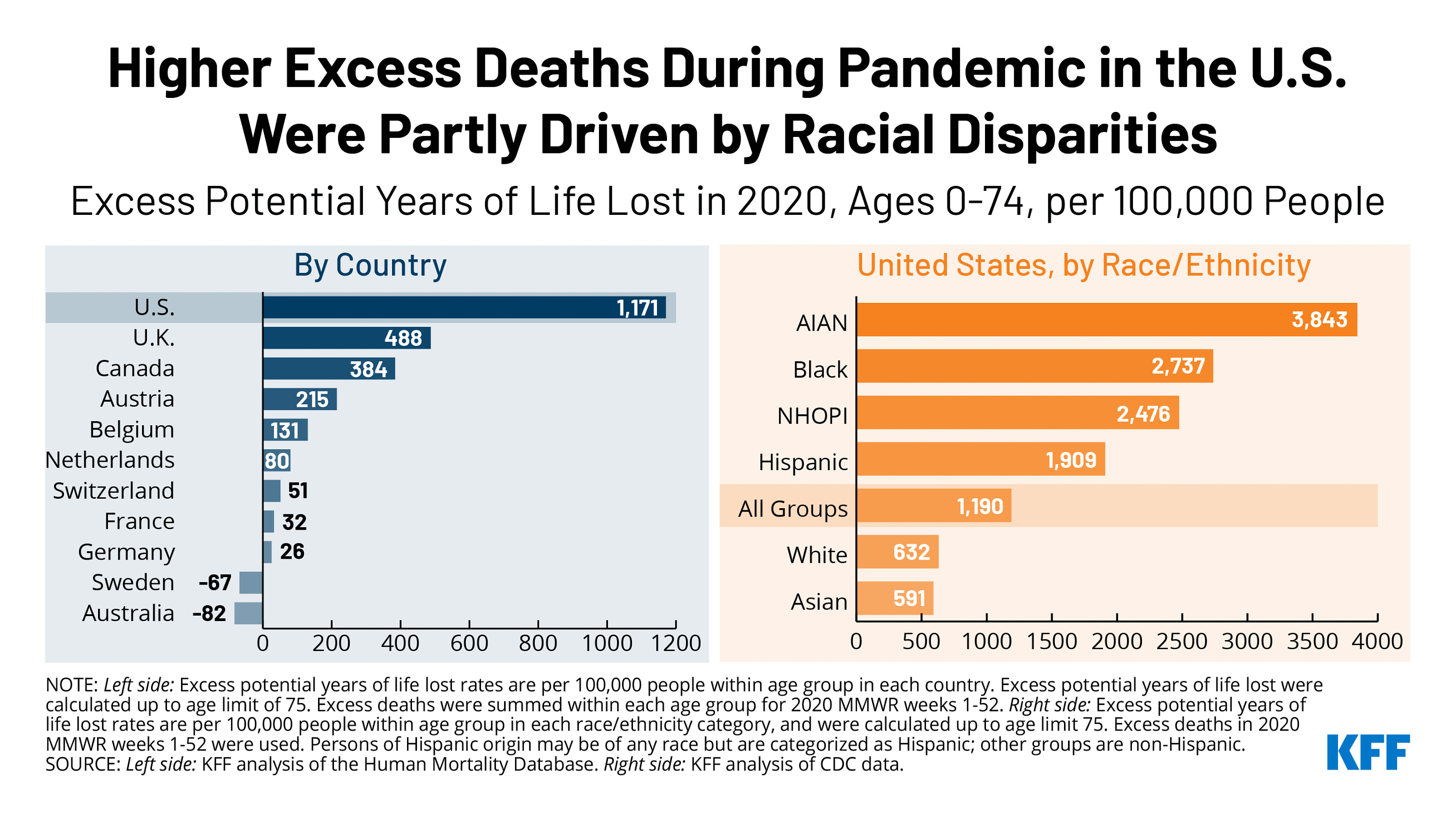

The US reported the highest rate of COVID associated deaths in the world, in spite of it’s public health strategies to deal with the pandemic and highly developed health care system. Racial disparities between nations also became clear. From late January to early October 2020, the US had 299,000 more deaths than the typical number during the same period in previous years. The largest percentages increases were among Hispanics, Latinos, Blacks and adults aged 25-44.

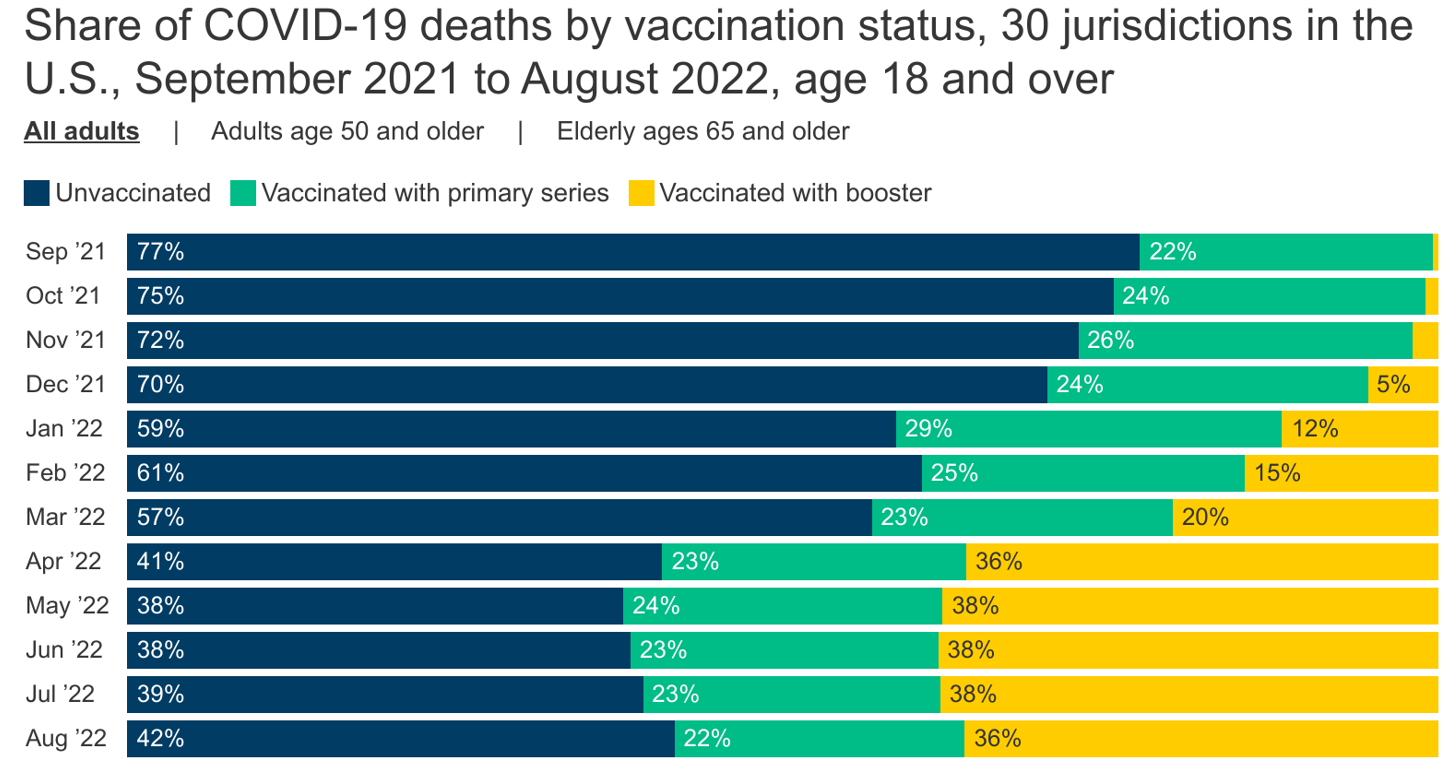

The percentage of COVID-19 deaths among those who are vaccinated rose over time. In fall 2021, about 3 in 10 adults dying of COVID-19 were vaccinated or boosted. But by January 2022, as shown below, about 4 in 10 deaths were vaccinated or boosted people. By April 2022, the CDC data show that about 6 in 10 adults dying of COVID-19 were vaccinated or boosted, and that’s remained true through at least August 2022 (the most recent month of data).

Emergency Department Structure, Staffing, and Triage

Emergency departments are often too small, poorly designed for current demands and flow, and under-staffed. Increasingly, ED patients are boarded there while under observation, waiting for imaging and lab reports, for procedures, or for an inpatient bed to become available. Once all the rooms and hallways in the ED are full, the waiting room fills up with ill people who may wait for long hours to see a provider. Local hospitals have also resorted to boarding patients on inpatient hallways.

In spite of initial triage by RNs who order basic lab, EKG or x-rays by protocol, studies since 2012 documented that it not uncommon for seriously ill people in the waiting room to have longer hospital stays and an increase in mortality by delays in care. This is a well- known triage problem world-wide. Most ED’s use the same triage data system to facilitate triage decisions, but clearly mistakes are made. Underlying chronic conditions other than the presenting acute problem may not be part of decision making to treat, admit or discharge. Ideally, triage could be completed by advanced practice nurses or PA’s who can perform more complex assessment and diagnosis.

Boarding has been identified as one of the primary causes and problems of ED overcrowding. I spent 3 full days on a gurney in a small room of the ED last week before being transferred to a hospital room. There were beds lining every hallway and a crowded waiting room with 5 patients on gurneys there too. One CNA told me about seeing an actively bleeding person in the waiting room with a blood- soaked towel applying pressure to a hand. Nurses from the floors were sent down to take care of 5 boarding patients each in the ED without the help of CNA’s, who were in short supply. Boarded patients often require a lot of care and monitoring for unstable health problems.

It was a bad week everywhere; hospitals in New York had to set up treatment tents in parking lots during that same week. Apparently, a number of newly arrived migrants arrived at the hospitals for care, including infant deliveries.

The ER nurses all spoke of there not being enough of them, referring to the influx of patients as “always bad.” There are not enough nurse practitioners and physician assistants either, who could certainly treat many of the more minor problems, perform procedures and order tests in collaboration with the ED doctors. The hospital closed its two urgent care centers due to lack of available staff, leaving fewer choices of places to go for acute problems.

Because there is no separate section in the local ED to manage ambulatory patients not needing critical care, a mix of patients and their family members line the hallways at busy times. Asante Rogue Regional Medical Center is a Level II trauma center with 24-hour in-house specialists and surgeons serving nine counties in Northern California and Southern Oregon. The ED has 2 trauma rooms, 20 exam rooms and 10 observation rooms. Not near enough for the busy flow of incoming patients. There are 4 nursing stations, staffed by 8 ER nurses. Not sure how many doctors. Imaging is directly across the hallway from the ED.

The hospital has been in the process of building a second 6 story tower the past four years, apparently experiencing a number of delays. The expansion will include beds for ICU, maternal/child, pediatrics, operating rooms and more space for the ED. Expansion plans include at least 5 other projects as well, adding an estimated new 200 job positions to fill. It currently has 378 beds.

Primary Care Referrals to ED

Increasingly, out-patient primary care and specialty offices, even urgent care clinics, send patients to the local ED when there is an urgent need for diagnostics, treatment or procedures. This is because it can days to weeks to obtain needed diagnostics through routine scheduling. Every health care facility’s phone is answered by instructing patients to call 911 for an emergency. At the cancer center, many patients are referred to the ED for chemotherapy related side effect assessment and treatment.

In my region of Medford, Oregon there are few primary care offices still accepting new patients, with the first visit scheduled months in the future. Specialty visits usually involve 3-5 months of waiting time for new patients, regardless of how ill the patient may be. Ill and injured people without a primary care provider, without insurance, or needing urgent care may have no choice other than an ED to obtain care. Medford is the only medium sized urban medical center for mostly rural or semi-rural regions from northern California to central Oregon, serving patients from over 200 miles away. Southern Oregon has a large and rising over 65 population, who tend to utilize health care services more than younger people.

Hospitalists now admit most patients for inpatient care, including surgery. About 70 percent of hospital inpatients are processed through the ED in the US. About 86 percent of ED patients were treated and released in 2018. The ED may also process patients transferred from other hospitals for admit. A key role of the ED is as the hospital’s gatekeeper. ED patients who need inpatient services require a disproportionate amount of time and energy from emergency physicians and ED staff. The most frequent diagnoses for hospital admission in the US in 2018 was septicemia, heart failure, osteoarthritis, pneumonia and other respiratory conditions and diabetes with complication.

Behavioral Health and Overdoses

Boarding of psych patients in the ED is a long-standing problem in many hospitals today. There’s a nationwide lack of inpatient mental health beds. The root of the problem is lack of funding for community mental health clinics. ED staff are often ill-equipped to address behavioral health needs, unless behavioral health specialists are assigned to the ED. And a patient with a behavioral health emergency requires more than three times longer than a patient with non-psychiatric needs, blocking at least two medical patients from receiving more timely care. The majority will be discharged without seeing a mental health professional. More often than not, lack of availability of beds and services outside of the ED prohibits the effective treatment of behavioral health patients.

The Uninsured and Migrant Populations

A patient is typically required to provide insurance and payment information before seeing a doctor. But emergency departments are unique—anyone who has an emergency must be treated or stabilized, regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay. The patient protection that makes this possible is a federal law known as the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA).

EMTALA was enacted by Congress in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) of 1985. EMTALA was initially designed to prevent hospitals from transferring uninsured or Medicaid patients to public hospitals without, at a minimum, providing a medical screening examination to ensure they were stable for transfer.

This law requires Medicare-participating hospitals with emergency departments to screen and treat the emergency medical conditions of patients in a non-discriminatory manner to anyone, regardless of their ability to pay, insurance status, national origin, race, creed or color. CMS defines a dedicated emergency department as “a specially equipped and staffed area of the hospital used a significant portion of the time for initial evaluation and treatment of outpatients for emergency medical conditions.” This means, for example, that hospital-based outpatient clinics and urgent care centers not equipped to handle medical emergencies are not obligated under EMTALA and can simply refer patients to a nearby emergency department for care.

The hundreds of thousands of migrants crossing the US open southern border during the Biden administration has stressed American hospitals as asylum seekers present themselves in large numbers to ED’s for emergent care, including childbirth.

Uncompensated care is a legitimate and significant practice expense for emergency physicians.

· Approximately 95.2% of emergency physicians provide some EMTALA-mandated care in a typical week and more than one-third of emergency physicians provide more than 30 hours of EMTALA-related care each week.

· According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 55% of an emergency physician’s time is spent providing uncompensated care.

· Despite comprising just 4% of all US physicians, emergency physicians provide two-thirds of all acute care for the uninsured and half of it for Medicaid patients.

· Medicaid care is severely underfunded and reimbursement rates often do not cover overhead costs of providing care, much less the physician’s time.

· Medicare coverage also falls short. Adjusted for inflation in practice costs, physician reimbursement has actually declined 19 percent from 2001 to 2018.

There is a popular perception that insurance coverage will reduce overuse of the emergency department. Both opponents and advocates of expanding insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have made statements to the effect that EDs have been jammed with the uninsured and that paying for the uninsured population’s emergency care has burdened the health care system as a result of the expense of that care.

However, evidence shows that insurance coverage increases ED use instead of decreasing it. Two facts may help explain this unexpected finding. First, insured and uninsured adults use the ED at very similar rates and in very similar circumstances. And the uninsured use the ED substantially less than the Medicaid population. Second, the uninsured do use other types of care much less than the insured.

One of the common arguments in favor of expanding health insurance coverage is that it can relieve ED crowding and reduce medical costs by shifting care to more efficient primary care settings, but that is not supported by research. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment was a randomized controlled evaluation of the impact of expanding Medicaid to cover uninsured working-age adults. It found that Medicaid coverage increased ED use across a broad range of visit types, conditions, and subpopulations and that this increase persisted over the two years of the study.

In another literature review, researchers analyzed data on more than 41,000 adults from 2013 and found that uninsured patients visit the ER about as frequently as insured patients, with 12.2% of the uninsured visiting the ER compared to 13.7% of insured patients. Uninsured people were less likely than those on Medicaid to go to the emergency department, compared to 29.3% of Medicaid enrollees who went to the ER for care.

Categories of Reasons for ED Utilization

There is a wide range of reasons that individuals seek care in an ED beyond emergent and urgent conditions, although there is a lack of consensus on appropriate use and definition of “emergency”. Here are a few:

· Lack of insurance (see above details)

· Easy access or convenience at night or weekends

· Lack of primary care

· Referral by primary care provider and other providers. Physicians often refer patients to EDs when their offices are overbooked, or when their patients could benefit from the testing and services provided by EDs, particularly during non-business hours.

· EDs are often utilized to perform the initial evaluation and processing of patients admitted to the hospital, accounting for nearly half of all hospital admissions.

· Homeless, mentally ill, and addicts tend to be superusers

· Injuries and trauma

· Social determinants

Social Determinants of Population Health and ED Utilization

Social determinants of health (SDH), defined as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, are strong predictors of morbidity and mortality. SDH are shaped by the distribution of money, power, resources at global, national, and local levels and have significant effects on individuals’ quality of life, morbidity, and life expectancy. SDH encompass social risks, conditions that put an individual at higher risk for poor health, such as poverty, as well as social needs, the actual needs recognized by an individual at a given time, such as lack of housing.

The CDC further categorizes SDH into five domains: economic stability; education access and quality; healthcare access and quality; neighborhood and built environment; and social and community context. Although separately categorized, these five domains impact one another rather than acting as isolated entities.

Health care systems struggle to integrate non-medical factors into their data and processes of care. SDH are crucial for understanding biomedical outcomes and health care utilization. Emergency departments, in particular, function like the canary in a coal mine and a window into the community by providing safety nets for the American health care system. The ED is mandated to provide evaluation and treatment regardless of patients’ social or financial background. To this end, millions of Americans impacted by social risks and social needs rely on the ED for both routine and urgent medical care

For example, adverse SDH such as homelessness and unemployment are strongly linked to attempted suicide, which leads to greater emergency department utilization. The homeless tend to visit the ED at a rate three times higher than the US norm. Lower social support and unemployment are also associated with frequent ED use.

SDH and COVID-19

People diagnosed with COVID-19 have faced employment challenges and large medical bills. These sudden economic shocks can increase morbidity and mortality, especially within the realm of mental health. Beyond the health effects caused by the disease, COVID-19 precipitated economic disruptions throughout the country. With this came unprecedented unemployment rates, loss of insurance, and severe economic hardships, especially among low-income populations.

The effects of the pandemic on SDH may be viewed through the lens of social vulnerability. Social vulnerability refers to the potential negative effects on communities caused by external stressors on human health. Such stressors include natural or human-caused disasters, or disease outbreaks. Vulnerable and at-risk populations have been shown to be most likely to seek care through the emergency department. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the relationship of our traditional health views with the importance of understanding the impact of social determinants of health on overall well-being at both at individual and population health levels.

SDH and Childhood Injuries

Injuries are the leading cause of death among children and youth in the United States. According to the CDC, for every child injury death, 25 children are hospitalized and another 925 are treated in an emergency department. Pediatric injuries represent a major concern to society and to the public.

Unlike ambulatory care, injuries are less amenable to prevention through clinical interventions and are more likely to be related to patient characteristics and social and environmental factors. In the United States, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and environmental characteristics have been shown to be risk factors for childhood injury. Minority racial/ethnic status and community-level socioeconomic disadvantage have also been linked to higher overall pediatric ED use, perhaps due to lack of access to a primary source of care.

Social Emergency Medicine

Unfortunately, most health care systems in the US do not adequately document SDH in electronic health records (EHR), so understanding how SDH are linked to acute, high-cost care utilization, such as emergency departments, is largely unexplored. The emergence of social emergency medicine (SEM) has been described as a concerted effort to counter the impact of negative SDH by expanding the role of emergency medicine to also diagnose and treat social determinants of health, rather than focusing solely on a biologic model of health.

To create a more just and equal system of health care, some hospitals across the country are expanding the use of screenings for SDH. For example, New York-Presbyterian, a comprehensive, integrated academic health care system with 10 campuses and over 3.2 million patient visits annually, recently launched a SDH screening initiative across seven EDs with the goal of identifying and addressing underlying social needs in the community it serves, along with improving healthcare equity.

Consequences of ED Overcrowding

· Lack of integration and coordination between inpatient and outpatient care

· Lack of continuity care for the patient

· Many gaps in providing holistic care

· Increased cost of outpatient care (treated and released patients)

· Lack of preventive care and management of chronic conditions

· Lack of collaboration between public health interventions and individual health care

· ED discharge of patients who need inpatient services for safety, effectiveness, monitoring and continued treatment

· Delayed care while in ED resulting in increased morbidity and mortality

· Inadequate hospital admits due to insufficient ED boarding space and inpatient capacity

Integration of care means that services are coordinated throughout prevention, treatment, and maintenance levels. Care also should be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient and equitable. The ability of the health care system to deliver on those elements goes a long way towards determining population health. Unfortunately, there are many barriers to quality health care in the US. There are large gaps in the integration of public health, environmental health, social determinants and hospital services.

The ED role of efficient treatment and release for acute care needs does not address chronic illness needs well. It does not address home care needs, provide counseling about lifestyle choices, or education for preventive and well- being measures. It does not establish a therapeutic relationship, so important for patient education and motivation. There is no continuity of care nor of being seen by the same provider who knows and understands the patient as a whole emotional and spiritual person with an occupation, family and purpose in life. Referrals for on-going care often lacking.

Costs of ED Boarding Economics of Holding Units

For hospitals operating at nearly full capacity, a bottleneck in the ED develops. Without available inpatient beds, the ED has nowhere to offload admitted patients. Unlike inpatient units, which accept patients until beds are filled and then stop, the ED cannot close the door. EDs, are then forced to board patients in less-than-ideal treatment areas, such as hallway beds.

Extended boarding periods in the ED can be harmful to clinical care and have significant financial costs and recognized nationwide to be a severe problem. Boarding delays incoming patients from being treated, leads to increased left without being seen rates, and increases the rate of patients leaving against medical advice.

By 2009, more than 90% of ED providers reported that they are operating at full ED occupancy on a consistent basis with a worsening crisis of ED crowding. Crowding occurs “when the identified need for emergency services exceeds available resources for patient care in the ED, hospital or both.” On average, patients wait almost three hours more for an inpatient bed in crowded EDs as compared to those that are not constricted by crowding, according to the Joint Commission (JCAHO). Crowding correlates with undesirable consequences, including delays in definitive treatment, increased mortality in the critically ill, and increased rates of complications leading to poorer patient outcomes.

Multiple surveys show ED providers consistently ranking ED crowding as their most important patient safety concern. JCAHO identifies over one half of all “sentinel events” in cases leading to morbidity and mortality to be the result of delays in treatment in hospitals. One third of such events could have been attributed to crowding. Boarded patients viewed as non-critical receive little nursing or physician attention in some cases.

A 2017 study showed that personnel costs per patient bed-hour were $58.20 for the ED, $24.80 for an inpatient floor, $19.20 for the inpatient observation unit, and $10.40 for an admissions holding area. The expense per ED bed-hour is more than twice that in non-critical care inpatient units. The study authors proposed opening an additional admission holding unit for non-critical, boarded ED patients for cost savings and allowing treatment of more incoming ED patients.

Crowding can be conceptualized as the relationship between the need for service and available resources. Several solutions have been proposed to alleviate the problem of boarding, including adding additional personnel or additional ED bed space, using observation units, ambulance diversion, and eliminating non-urgent ED referrals. However, these proposed solutions are problematic. Adding additional personnel is not always an option. And it has been shown that simply increasing the number of available ED bed space, without a concomitant increase in the number of providers, does not have a substantial effect on boarding or overall patient satisfaction.

ED Overcrowding Solutions

Because ED overcrowding has been going on for decades, many studies and proposals have been made. Here is a reference from 2016 describing a number of proposed solutions.

Disclaimer: We at Prepare for Change (PFC) bring you information that is not offered by the mainstream news, and therefore may seem controversial. The opinions, views, statements, and/or information we present are not necessarily promoted, endorsed, espoused, or agreed to by Prepare for Change, its leadership Council, members, those who work with PFC, or those who read its content. However, they are hopefully provocative. Please use discernment! Use logical thinking, your own intuition and your own connection with Source, Spirit and Natural Laws to help you determine what is true and what is not. By sharing information and seeding dialogue, it is our goal to raise consciousness and awareness of higher truths to free us from enslavement of the matrix in this material realm.

EN

EN FR

FR