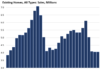

The charts are brutal.

By Wolf Richter,

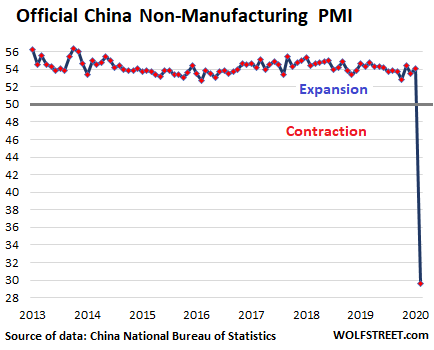

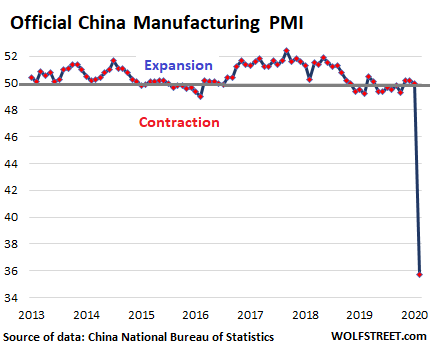

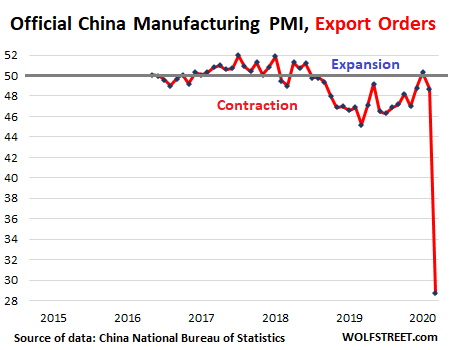

Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) are a tally of how executives see their own company – whether business activity at their company rose or fell compared to the prior month, whether new orders rose or fell, whether they added or shed staff, etc. Executives and their companies remain unnamed. A value above 50 means expansion; a value below 50 means contraction. PMIs are an early indication of business conditions – and by extension, of the economy.

And in China, both, the PMI for the non-manufacturing sector and the PMI for the manufacturing sector, released on March 1, have collapsed to unfathomable lows, showing to what extent the measures to impede the spread of the coronavirus have shut down the economy.

Even non-manufacturing activity collapses.

The official Non-Manufacturing PMI, released by the National Bureau of Statistics, collapsed from 54.1 in January (still well into expansion mode) to a previously unthinkable low of 29.6 in February. The horizontal gray line at 50 in the chart indicates stagnation. Below 50 means contraction. Since 2007, China’s non-manufacturing sector has grown every single month. Until February:

The non-manufacturing PMI is broader than just services. It also includes the retail sector and construction. Here are some other standouts:

- New orders plunged to 26.5, with export orders plunging to 26.8

- Employment, which had already been in contraction in January (48.6) dropped to 37.9

- Input prices fell to 49.3 (from 53.3)

- Output prices fell to 43.9.

- Confidence plunged from 59.6 in January to 40.0 in February.

Manufacturing collapses, but it’s worse than it looks.

The official China Manufacturing PMI, released by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, had already been either in the doldrums or in outright contraction for the past 14 months. In January it was at 50.0, the stagnation point. In February it collapsed to a previously unfathomable 35.7:

But it’s even worse than it looks, as the index was likely distorted to upside, due to the way a sub-index, “supplier delivery times,” is figured into the headline PMI, according to Lu Ting, chief China economist at Nomura Holdings in Hong Kong.

The headline PMI is based on a number of sub-indices. One of them is “supplier delivery times,” which accounts for 15% of the headline PMI. Normally, when supplier delivery times rise, it’s a sign of strengthening conditions in the manufacturing sector: there is a lot of demand, and suppliers are struggling to meet that demand. So longer delivery times add to the headline PMI index value.

But this time, the supplier delivery times rose because the transportation system was partially shut down, travel bans had been imposed, entire cities had been locked down, and many suppliers were shut down. With manufacturers’ supply chains cut to shreds, factories had trouble getting components and supplies.

According to Nomura’s report, if the supplier delivery times index hadn’t surged, but had remained at the same as in January, the headline PMI index would have dropped to 33.

And the sub-index for manufacturing exports orders collapsed to 28.7:

This plunge in the non-manufacturing PMI and the manufacturing PMI shows the mindboggling extent to which China’s economy has been disrupted by the coronavirus-containment methods in February.

And there is something else.

Friday evening, the homepage of the English-language website of the National Bureau of Statistics of China where I normally get the PMI data was still accessible, but the page with the data for the PMIs was not accessible and showed a “502 Bad Gateway” error. And this problem persists as I’m writing this on Saturday evening (Sunday in China). This is a screenshot:

I’m not going to over-interpret this 502 Bad Gateway issue. It’s not a rare issue on the internet. What is rare is that a major website operator, such as the Chinese government, hasn’t gotten around to fixing it after more than 24 hours!

It could be another sign of how disrupted everything is, with people that normally take care of a problem immediately not being at work, but being in quarantine, or being told not to leave their home, or being stuck in their ancestral village.

And there are likely many of these problems that would normally get fixed quickly, that now don’t get fixed because there is no one there to fix them. This particular 502 Bad Gateway issue is trivial, but many other issues that aren’t getting fixed might not be that trivial.

ANZ banking group estimated, based on migration data of workers returning to the city from their villages, that about 50% of the workers had returned to their jobs as of this weekend, but that China’s economy was operating at only 20% capacity, hampered by issues ranging from lacking parts to other workers not having returned to work. But work resumptions are rising rapidly, ANZ said, and the March PMIs are expected to bounce off those catastrophic lows.

Source: WOLF STREET.

Disclaimer: We at Prepare for Change (PFC) bring you information that is not offered by the mainstream news, and therefore may seem controversial. The opinions, views, statements, and/or information we present are not necessarily promoted, endorsed, espoused, or agreed to by Prepare for Change, its leadership Council, members, those who work with PFC, or those who read its content. However, they are hopefully provocative. Please use discernment! Use logical thinking, your own intuition and your own connection with Source, Spirit and Natural Laws to help you determine what is true and what is not. By sharing information and seeding dialogue, it is our goal to raise consciousness and awareness of higher truths to free us from enslavement of the matrix in this material realm.

EN

EN FR

FR