By Elaine Buxton

Introduction

Periods of extended drought over the past 22 years, along with climate warming in the southwestern United States, is the most severe in over 1,200 years, and is not predicted to improve significantly. Using southern California’s largest metropolitan region, Los Angeles County as an example, this series on water shortage examines the water issues, water sources, governing systems and water management infrastructures in Parts 1 and 2. All of it is complex but necessary to understand for anyone who wants to participate, or at least be informed, about how water resources are going to affect all of our lives in the immediate future. Part 3 focuses on policies and solutions for better water management, water quality, efficiency, and equity across urban, agricultural, environmental, and recreational sectors.

Without any capacity to save water during wet times for use in drier times, agriculture, industry and support for large urban populations in many regions would not be possible. In 1922, The Colorado River Compact agreement forecast that 15 MAF of water would be available annually to divide up between the 7 upper and lower basin states. Now drought and climate change has reduced that flow to 12.3 MAF, requiring drought contingency plans. On June 14, 2022 at a US Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources hearing, USBR Commissioner Camille Touton informed the 7 states that they must come up with a plan by mid-August to conserve 2 to 4 MAF in 2023, or the USBR will impose its own solutions on the states. Until this year, Southern California has received 15 percent of its water supply from the Colorado River. This means time is running out to implement water conservation measures. The upper basin states claim that they have already done their part, and the rest must be reduced by the lower basin states.

Water shortages are not purely a function of hydrology and climate: shortages are a function of supply not meeting demand, how water is used, watershed infrastructure, and adaptability. The human component is how water resources are managed to create resilient natural systems that can weather normal cycles of low precipitation. California still has considerable untapped potential to reduce demand and increase supply. In comparison, Nevada and Arizona appear to be more prepared.

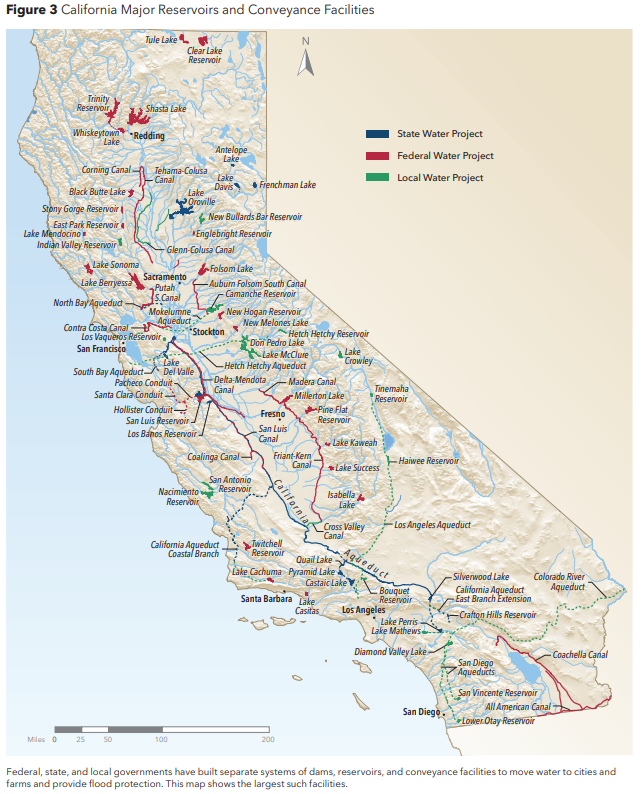

Since 1900, California’s water supply strategy has largely relied upon building reservoirs for storage, conveyance systems for diverting surface water, and drilling into underground aquifers. Hundreds of billions of dollars have been invested in these options, but now it is tapped out and unsustainable. The rivers are over-allocated, the groundwater is over-drafted, the land is sinking over depleted aquifers and canals and delta ecosystems are severely damaged. The good news is that there are cost-effective and technically feasible solutions compatible with healthy rivers and groundwater basins, as well as creating new sources of water for human consumption.

Philosophical, Biological and Social Principles

The following principles are essential considerations for resilient and equitable water supply:

- We all have a basic human right and need for clean drinking water.

- We are responsible for good stewardship of Earth’s natural resources and wildlife habitat.

- We need to grow healthy, nutritious food to survive.

- Industrial and agricultural pollution must be limited and cleaned up when it occurs because it adversely affects the needs stated above.

- Good groundwater aquifer management is equally important to surface water management to create and maintain water resilience.

- Energy, climate and water are really all the same considerations.

- Assuming that the people in powerful positions are always right, scientific experts, and represent all communities equally, is a fallacy.

- We cannot take water for granted, even though there is enough water on Earth to support us all.

New Strategies and Options

While regional differences apply, it was estimated in a study by the Pacific Institute and NRDC that the following conservation measures could provide 10.8 to 13.7 MAF annually in new water supplies and demand reductions for California (The Untapped Potential of CA’s Water Supply: Efficiency, Reuse, and Stormwater, June 2014, PI, NRDC).

- Water reuse and recycling of treated wastewater.

- Expanded stormwater capture to reduce pollution and for recycling of treated water.

- Modernizing agricultural irrigation practices to increase efficiency by 17 to 22 percent

- Improve urban use efficiency by repairing leaks in underground pipes, installing efficient appliances, use of grey water, and adopting drought tolerant landscaping plants.

The 2021 to 2030 goal at Pacific Institute is to catalyze a transformation to water resilience in the face of climate change.

Pacific Institute defines water resilience as the ability of water systems to function so that nature and people, including those on the frontlines and disproportionately impacted, thrive under shocks, stresses and change.

Water systems include natural and man-made environments as well as the social and governance systems that support them. The term function refers to services and processes that maintain a natural environment. Stresses and shocks refer to events and long-term trends affecting the systems. Resilience must also be persistent, adaptable and transformative as shifts occur. All people and the environment must have water security and sustainability of enough supply to thrive now and in the future.

Equity of Water Rights

The key equity concepts and strategies for 2022 at Pacific Institute are as follows:

- The US has not fully adopted the Human Right to Water law passed in 2012, as demonstrated by the millions of people who lack access to clean, reliable water or basic plumbing and persistent violations of water systems for safe drinking water.

- Throughout the world, water insecurity and climate change disproportionately affect disadvantaged, low income, homeless, color minorities and rural communities. They suffer the most from environmental injustices related to climate change and water shortages for drinking, cooking and sanitation. They may be left without water when wells run dry. Not uncommonly, low-income housing units become so contaminated they must use bottled water.

- Research and outreach efforts on the behalf of the above populations with real water insecurity needs to be addressed by decision makers in a collaborative approach.

Small acreage farmers, farmers of color, tribal farmers and tenant farmers have been underrepresented under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act plans submitted to DWR in the first round. CRIT leaders want a seat at the decision-making table regarding Colorado River water. And as the state expands it plans to offer farmers incentives to fallow their land by selling water rights or other repurposing, their tenants could be casualties of that process. Farmers also need assistance for shallow wells that have dried up, along with farm workers who have lost jobs when land is fallowed.

Dating back to the 1800’s, California has a history of discriminating against Mexican, Latino, Indian and Asian workers by denying them property and water rights in the California Land Claims Act of 1851 and the Alien Land Law of 1913 and 1920. Native American people were removed from their land or killed to make room for white settlers. To this day, the federal and state water rights system of senior versus junior levels denies many people equal access to the natural public resource of water and ignores the right to clean drinking water and a healthy river environment in some regions of the country. It is an exclusionary set of policies that some groups view as racist. The first come, first serve approach of water rights is no longer justified, if it ever was. “Reasonable” uses of water, management and equity is long overdue.

Pollution Prevention

Before disinfection of water supplies became a common practice around 1925 in the US, widespread outbreaks of cholera and typhoid were frequent. Now drinking water supplies are heavily regulated for public and private water suppliers, requiring tremendous amount of time, testing, and technology to make surface water safe to drink. Other perils include natural sulfur, zinc or arsenic contamination. Groundwater can absorb pollutants from fertilizers, septic tanks, mine drainage, fracking, industrial chemicals and metals, stormwater, and harmful drugs and microorganisms from people and animals. Agricultural nitrate runoffs have been in the news lately because it is harmful if it enters the drinking water supply. Nitrates and salts from irrigation and fertilizers can also destroy soil health. For decades, growers, water providers, regulators and universities have recognized the salt and nitrate problems in the soil and groundwater of the Central Valley in CA.

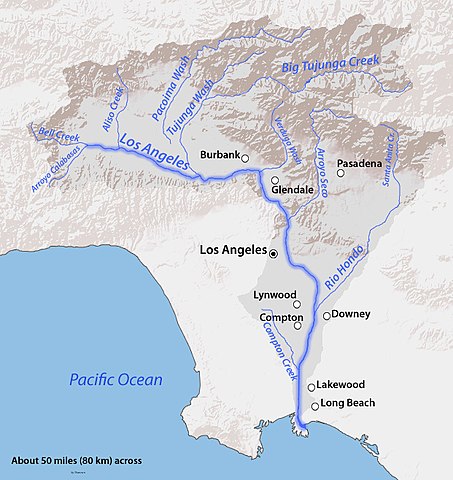

2022 is the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act (CWA), yet we have a long way to go. According the Los Angeles Waterkeeper, LA has an astounding 100 billion gallons of annual runoff carrying pesticides and herbicides from homes, oils and grease from roads, heavy metals and toxins from industries, trash, and bacteria that threatens public health and the environment.

The majority of waterways in LA County are polluted, with rivers and creeks serving as concrete flood control channels rather than as vibrant habitats. The LA River is one example of this. One of LA Waterkeeper’s priorities is to focus on regulatory and legal enforcement around industrial and urban stormwater runoff regulations, education and advocacy. Over the past two years, they identified a dozen polluting industrial facilities in LA, bringing them into compliance with Clean Water Act standards through legal settlements.

The majority of waterways in LA County are polluted, with rivers and creeks serving as concrete flood control channels rather than as vibrant habitats. The LA River is one example of this. One of LA Waterkeeper’s priorities is to focus on regulatory and legal enforcement around industrial and urban stormwater runoff regulations, education and advocacy. Over the past two years, they identified a dozen polluting industrial facilities in LA, bringing them into compliance with Clean Water Act standards through legal settlements.

In 2001, the LA Regional Board adopted the stormwater MS4 permit to regulate discharges from LA County, the County’s Flood Control District, and 84 cities. Unfortunately, in 2012 the LA Regional Board offered a huge loophole in the MS4 permit renewal process called a “safe harbor” provision in which municipalities could be in compliance by merely having plans to reduce runoff. The loophole was again extended in 2021. As a result, very little progress has been made in watershed water quality. LA Waterkeeper has spent over 10 years advocating for a more enforceable permit and will continue to do so.

LA Waterkeeper uses a “4R” (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Restore) approach for the provision of local water supplies. That translates into advocating for greater conservation, stormwater reuse, wastewater recycling, and groundwater replenishment. They oppose high energy, expensive ocean desalination projects that cause harm to the ocean and marine life.

Urban Water Conservation and Efficiency

About half of California’s urban water use, 4.2 MAF, is outdoor landscaping, washing cars and sidewalks, and filling pools. Therefore, outdoor water conservation can yield significant savings. Beginning in 2015, governor executive orders and DWR ordinances required new landscape efficiency, new plumbing EPA efficiency standards for bathroom fixtures, and a rebate program was established to replace inefficient appliances.

However, there were several shortfalls in the regulations, such as excluding large-lot, suburban yards and golf courses from reductions and not requiring rainwater and stormwater collection in new developments. Pool covers greatly reduce water evaporation and need for refilling.

However, there were several shortfalls in the regulations, such as excluding large-lot, suburban yards and golf courses from reductions and not requiring rainwater and stormwater collection in new developments. Pool covers greatly reduce water evaporation and need for refilling.

In general, large cities with multiple water storage infrastructures are in far better shape than small rural communities that depend on wells that go dry during drought. An editorial article in the LA Times on 7/31/22 reported how several large buildings and garages with belowground levels are having to pump out flooding from their lower levels and elevator shafts due to a currently high-water table. (High water tables dot LA areas, LA Times, 7/31/22)

Agricultural Conservation and Efficiency

Agriculture uses 60 to 80 percent of California’s developed water supplies, depending on the region. As of 2015, half of irrigated acreage was still using flood and furrow methods instead of more efficient drip irrigation and other methods such as cover crops. The state has not set goals or mandatory requirements for agricultural water conservation, although rising cost of imported surface water and groundwater monitoring may motivate changes. Modernizing irrigation methods can cut water use by almost 30 % without fallowing large tracts of farmland.

Agriculture uses 60 to 80 percent of California’s developed water supplies, depending on the region. As of 2015, half of irrigated acreage was still using flood and furrow methods instead of more efficient drip irrigation and other methods such as cover crops. The state has not set goals or mandatory requirements for agricultural water conservation, although rising cost of imported surface water and groundwater monitoring may motivate changes. Modernizing irrigation methods can cut water use by almost 30 % without fallowing large tracts of farmland.

Water suppliers and pumpers for agriculture and urban use were required to submit water use and water efficiency plans to the DWR since the Water Conservation Act (SB X7-7) was passed in 2009. The DWR was responsible for implementing 18 projects. However, by August 2013 only 25 of 79 agricultural water suppliers had submitted plans, or a 30 percent compliance rate. In May 2015, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) sued the DWR to enforce existing laws for water security.

NRDC reports that the state has many tools to improve agricultural irrigation efficiency, but has failed to utilize many of them. For example, water delivery spills can account for up to 20 percent of a water district’s total water use. The state could set standards for irrigation delivery by suppliers. The state could clearly define what are wasteful practices and enforce violations. It could develop policies and requirements for soil health, such as using cover crops and no-tilling that reduces the need to irrigate as frequently by 30 percent for each approach. The state could adopt conservation-based pricing for water delivered to State Water Project (SWP) contractors.

Since the 1930’s, the US Congress has enacted 18 farms bills, typically reauthorized and updated every five years, last signed by President Trump for 2018-2023. The farm bills govern a wide array of agricultural and food programs, implemented, monitored and financed for 5 to 10 years by the US Dept. of Agriculture (USDA). Programs include commodities, nutrition assistance (SNAP), horticulture, bioenergy, conservation, research, rural development, forestry, energy, crop insurance and trade in 12 titles. Nutrition by far has the largest budget for 2018-2023. Grants for rural water, waste disposal and wastewater programs are under Title VI for Rural Development.

The California Dept of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) has a long list of programs with the overall mission to protect and promote safe and healthy food supply, trade, and environmental stewardship. CDFA’s Environmental Farming section has healthy soil and water efficiency programs such as SWEEP. SWEEP, the State Water Efficiency and Enhancement Program, provides grants to implement irrigation systems that conserve water. The CA State Board of Food and Agriculture, is a 15-member advisory board to the governor regarding key issues important to farmers and ranchers, community stakeholders, and citizens. Public participation in all matters concerning agriculture and food policy is encouraged.

Stormwater Capture Programs

NRDC and Pacific Institute estimate that capturing urban stormwater runoff in southern California and San Francisco can increase water supplies by up to 630,000 AF annually while reducing a leading cause of pollution. This could be done by directing stormwater runoff to open spaces, thereby recharging groundwater supplies. Rainwater could be harvested from rooftops and used as grey water for direct non-potable uses. While the SWRCB set goals for stormwater collection goals in its Storm Water Strategic Initiative of 2013, both SWRCB and the DWR have generated few projects to meet those targets in spite of their own written plans to do so. In 2018, LA voters approved Measure W (Safe Clean Water Program) which provides $280 million per year for multi-benefit stormwater projects.

Because the state has failed to strengthen and enforce existing stormwater capture programs, NRDC teamed up with Los Angeles Waterkeeper to file ligations in 2008 and again in 2012 against the County of Los Angeles and its Flood Control District for violations of their stormwater permits by providing safe harbor exemptions. However, the SWRCB upheld the exemptions in 2015. Urban stormwater runoff is considered the top source of coastal water pollution in California, fouling drinking water, ecosystems and waterways. It is also a missed opportunity to increase local water supply. For example, one-inch of rain in Los Angeles County can generate 253,437 AF, or nearly 40 percent of LA’s annual water use. Funding and eligibility guidelines for stormwater management has been insufficient for the projects.

Recycled and Reused Water

Water reuse holds tremendous potential for drought resistant water supply. In 2010, California was using 670K acre feet of reused municipal wastewater. In 2014, the SWRCB increase funding for recycled water to develop an additional 150K acre-feet. SWRCB also adopted regulations and funding for expanding recycled water to replenish groundwater, along with monitoring and other public health measures. Existing law requires the SWRCB to also adopt regulations for augmenting surface water supplies, such as in reservoirs. Unused wastewater is still treated and discharged directly into the ocean. Florida prohibited south Florida wastewater treatment plants from discharging directly into the ocean by 2025, claiming it could be reused for beneficial purposes. The same could be done in California.

Homes and businesses could use greywater with little or no treatment instead of higher cost drinking water. For example, water from a clothes washer could be used to irrigate a garden or for flushing toilets. However, most municipalities lack effective standards and codes for the use of grey water. While water reuse can and should be expanded, it must also be protective of the environment to avoid unintended consequences. Some water districts have begun to offer rebates for exchanging laws for drought tolerant landscaping, which has been well received.

Groundwater Sustainability

Groundwater is a vital life source for all sectors of users in California, providing an average of 40 percent of water in normal to wet years of precipitation, rising as high as 60 percent in drought years. And some communities are 100 percent dependent on groundwater. Chronic over-drafting has led to multiple problems, including falling water tables, dry wells, land sinking, and poor water quality. Rural communities that depend on shallow wells that go dry in summer, exacerbated by curtailments of irrigation water, suffer more than large urban areas from drought related water shortages.

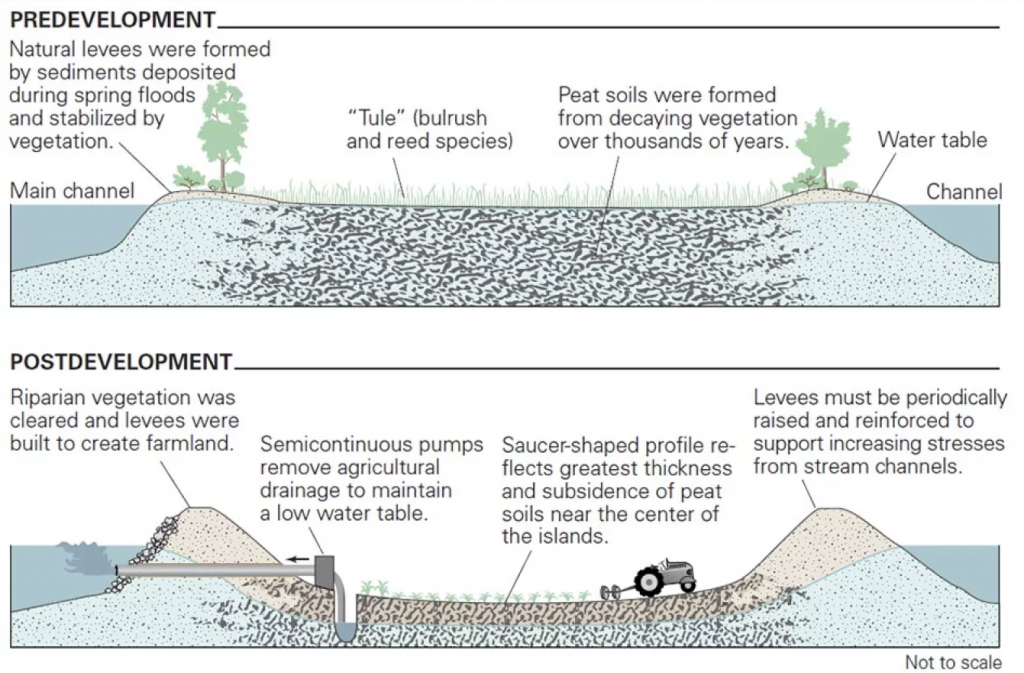

The floor of the Central Valley has been sinking as groundwater over-drafting depleted most basin aquifers, called subsidence, since surface water became unavailable for agricultural irrigation, as noted in the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Act (SGMA). SGMA requires local water agencies to bring the basin withdrawals and deposits into balance by 2040. Water agencies were also required to develop plans to monitor plumbing, recharging the aquifers and conserve water by July 2022. DWR rejected plans from 12 basins as incomplete on 1/28/22, but as of Aug 2, ten basin plans have been resubmitted and opened for public comment.

There is a wide range of strategies to replenish groundwater and protect it from contamination and pollution. Some of this is already described in other sections of this report for water reuse, stormwater capture, and pollution prevention. Stanford University’s Groundwater Program completed a study using groundwater data since the 1950’s and satellite technology, published in 2019, to provide a scientific basis for sustainable management. One of its findings was that compaction of thick clay layers account for 90 percent of the subsidence and will take decades to centuries to restabilize after the aquifers are replenished to higher levels.

Standford water experts, including Felicia Marcus, who was the SWRCB chair until Governor Brown replaced her with E. Joaquin Esquivel in 2017, identified the three most important areas for water investment as groundwater storage projects, wastewater recycling, and stormwater capture. They also note that rural communities are suffering the most from dried up shallow wells and local contamination of aquifers. The offer the following ways to assist rural communities.

- State rejection of large agricultural groundwater pumper plans to over-draw around domestic and small system wells

- Help small rural communities to hook up to larger basins that have more resources

- Recharge basins near shallow wells

- Drill deeper wells for small system and domestic well owners

- Establish water financing strategies.

There are considerable differences of opinion between scientists and stakeholders regarding watershed stressors and how to mitigate the stressors in order to achieve the 2040 goals in the SGMA, partly depending on how the stressors affects the stakeholder, according to two surveys in 2013 conducted by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC). Most scientists agree that habitat and flow alterations are most important in restoration of natural processes. Water exporters tend to consider low flows less harmful. Groups responsible for discharges of pollution and habitat alterations view those stressors as less harmful than Delta residents.

Farmland Repurposing

There is a scientific consensus that at least 500,000 to 1 million acres of irrigated farmland will need to be taken out of production and repurposed with lower intensity water use in the Central Valley in order to restore health to the Delta ecosystem. It is one of the fastest was to cut demand and balance aquifers. Which lands, how they are converted, for what purposes, and who bears the cost are outstanding questions. It is expensive to tear out an orchard, for example. The state Department of Conservation has two programs, begun in the past few years, for purchase of agricultural easements on farmland, Agricultural Land Mitigation Program, and Multi-benefit Land Repurposing (MLRP) that provide incentives to farmers suffering water shortages in several Central Valley counties. This allows farmers to retain some value to their land, rather than it sitting idle. MWD also pays farmers who receive Colorado River Aqueduct water to fallow farm acreage.

Retired farmland could be repurposed for a variety of uses such as solar facilities, grazing, open land for groundwater storage, or native wildlife habitat. Dry winter farming is another option, although less profitable for the farmer. Fallowed farmland should not become new sources of windblown dust as the soil dries out in a warming climate zone which would impact low-income rural communities and worker first and foremost. The San Joaquin Valley already faces ongoing air quality problems, worsened by wind and wildfire smoke and could be at risk of becoming another Dust Bowl that devastated the Great Plains in the 1930’s. (Land Transitions & Dust in the San Joaquin Valley, July 2022 Report, www.PPIC.org)

The total, overall loss of farmland acreage in California for surface and groundwater environmental sustainability also needs to be balanced with the need to produce food for a growing population. The Williamson Act of 1965 is a deterrent to farmland conversion by motivating farmland retention through reduced property taxes in exchange for an annually renewing 10-year commitment not to develop the land. A considerable number of California cities and counties have farmland retention policies. Finding a balance between competing interests and needs is essential.

Energy and Water

Water and energy are interdependent in a number of ways. Energy is needed to store water, get it to where it is needed, treat it for reuse, generate electricity and process raw materials in facilities. Electricity production from fossil fuels and nuclear plants accounts for 39 percent of all freshwater withdrawals in the nation. Agriculture is one of the highest consumers of energy in California. The energy costs of water diversions and treatment needs to be considered with construction of all new systems and facilities.

Water and energy are interdependent in a number of ways. Energy is needed to store water, get it to where it is needed, treat it for reuse, generate electricity and process raw materials in facilities. Electricity production from fossil fuels and nuclear plants accounts for 39 percent of all freshwater withdrawals in the nation. Agriculture is one of the highest consumers of energy in California. The energy costs of water diversions and treatment needs to be considered with construction of all new systems and facilities.

Extracting water from rivers or pumping it from aquifers, then transporting it long distances to storage facilities requires a highly intensive use of energy. The SWP is the largest single user of energy in California, consuming 2 to 3 percent of CA electricity to pump water over 700 miles. Additionally, water treatment facilities use energy to process water and then pump it to distributors. Water is used for cooling in large facilities such as hospitals, again using energy for circulating the water. Water delivery for residential, commercial, and industrial end-use uses the most energy at 11 percent, followed by agriculture at 3 percent, according to the CA Energy Commission.

Ocean Desalination Projects

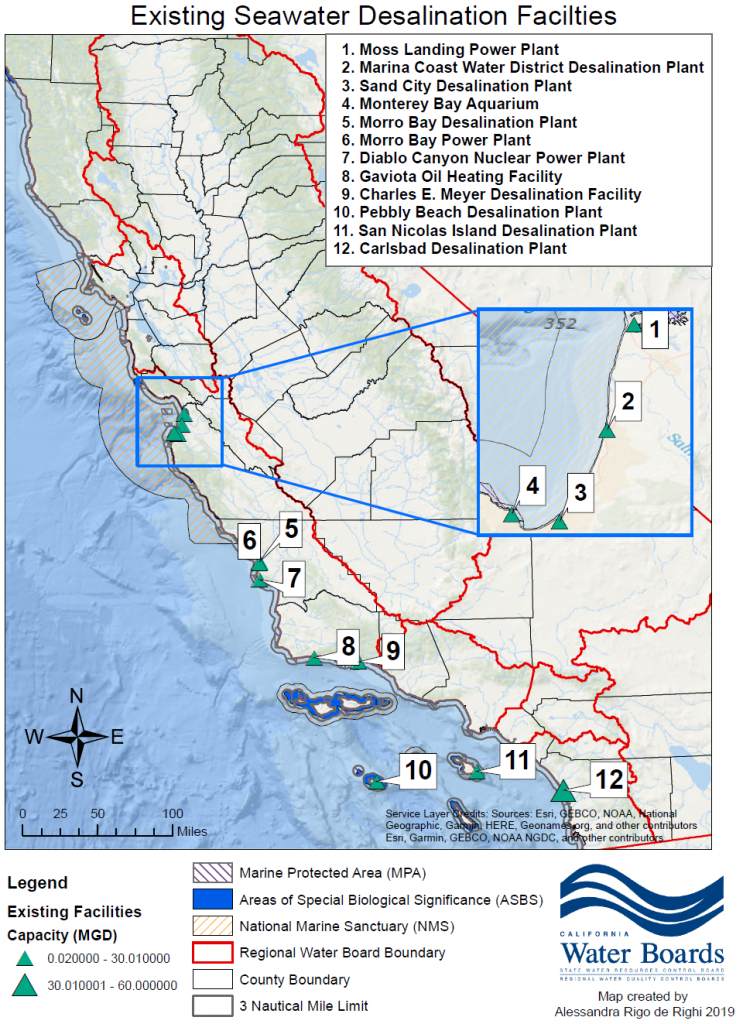

Ocean desalination is an energy-intensive, expensive and climate-impacting approach to water shortages with worse negative impacts than importing water from other regions. Intake pipes not only suck up water, they also suck up marine life. The byproduct of desalination is a salty brine that is toxic when dumped back into the ocean or landfills. The energy required to run facilities has a high carbon imprint. And desalinated ocean water costs twice as much as imported water and three times more than stormwater.

LA Waterkeeper worked with Smarter Water LA to stop West Basin Municipal Water District from building an ocean desalination plant on the shores of El Segundo in Santa Monica Bay between 2019 to 2021. In May 2022, plans for massive desalination plant in Huntington Beach were rejected by the California Coastal Commission due to concerns about high costs and environmental hazards.

On the other hand, smaller scale desalination plants around the world, particularly on islands that don’t have access to imported water, have been successful with far less harmful impacts on the ecosystem. There are 12-14 desalination plants in California, some part of treatment facilities not drawing out ocean water. Catalina Island off the coast of Long Beach, for example, has avoided disastrous consequences of the current drought using a desalination plan along with conservative measures such as salt-water toilet flushing. Brine discharges into the ocean range from 30 to 50 parts per thousand compared to average ocean salinity of about 35 parts per thousand.

On the other hand, smaller scale desalination plants around the world, particularly on islands that don’t have access to imported water, have been successful with far less harmful impacts on the ecosystem. There are 12-14 desalination plants in California, some part of treatment facilities not drawing out ocean water. Catalina Island off the coast of Long Beach, for example, has avoided disastrous consequences of the current drought using a desalination plan along with conservative measures such as salt-water toilet flushing. Brine discharges into the ocean range from 30 to 50 parts per thousand compared to average ocean salinity of about 35 parts per thousand.

Restoring the Delta Ecosystem and Its Water-Dependent Species

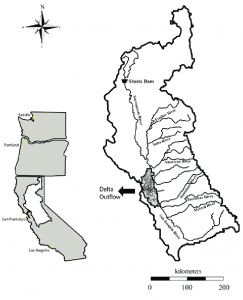

The Bay Delta is a crucial hub of California’s water system and ecological resource, through which the majority of water flows to the CVP and SWP systems. It is located at the junction of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers. The Delta is the largest freshwater estuary on the West Coast of the Americas, with the watershed providing about 40 percent of California’s freshwater supply. It provides vital habitat for migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway and for fish. It provides a rural way of living for people with historic towns, scenic roads, farms and recreational opportunities. Historically, it was the home of large populations of indigenous people, before large scale water projects built by the CVP and SWP converted marshland into farmland. It was recognized as a National Heritage Area in 2009.

Enough freshwater must flow through the Delta during dry months to prevent saltwater intrusions from San Francisco Bay. CVP and SWP reservoirs help control salinity that can contaminate water used by Delta residents and water exporters, but drought conditions have lessened available water to maintain water flows. Low freshwater flows cause an increase in algal blooms, which are highly toxic by causing oxygen dead zones and poisoning drinking water. Furthermore, Chinook salmon in the delta river basins have significantly declined since the late 1980’s and are now listed under the state and federal Endangered Species Act. And Delta Smelt survival, now near zero, is a key indicator of a watershed’s health as well. Since 2018, the Bay-Delta Plan requires 40% minimum unimpeded flow for the lower San Joaquin River and its tributaries, the Stanislaus, Tuolumne and Merced rivers. The actual flows due to minimum standard waivers have fallen below that.

In late July of 2022, CA Governor Newsom released the details of his plans for building yet another gigantic tunnel to divert more water from the Sacramento River and Delta to southern California cities at a cost estimate of around $16 billion in 2020 dollars. It is known as the Delta Conveyance Project. The tunnel would be 40 miles long, and take 14 years to construct. It’s stated purpose is to protect water quality for exporters due to rising salinity in the Delta but does not prevent the intrusions, and will, in fact, worsen the salinity problem. The plans are vague about the amount of water that will be exported and the remaining unimpeded water flow of Delta waters.

The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the Santa Clara Valley Water District and 14 other water agencies receiving State Water Project water have been funding the planning for a Delta tunnel system for decades. It was also supported by previous CA governors Brown and Schwarzenegger. Earlier proposals known as the Peripheral Canal, CALFED, Bay Delta Conservation Plan, and California WaterFix were defeated by opponents. The current version would be a single 36 feet diameter tunnel crossing the eastern side of the delta, then delivering water to the Bethany Reservoir in Alameda County near Livermore and the SWP pumping facility.

The Board of the Metropolitan Water District (MWD), the main water wholesaler in Southern California voted in April, 2022 to fund the next phase of the controversial Sites Reservoir with $20 million of rate-payers money. Sites Reservoir, if built, would be located in Glenn and Colusa Counties and exempted from California Environmental Quality Act standards. Sierra Club opponents point out the environmental negative consequences for local communities and that the project would facilitate construction of the Delta Tunnel by storing tunnel water. MWD also funded at least $60 million for planning of the Delta Conveyance Tunnel and adopted an increase of 5 percent for water ratepayers.

On July 27, 2022 the DWR released its Delta Conveyance Project Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR), which is available to the public for comments through Oct. 27, 2022 on its Delta EIR website. DWR is the lead agency which must comply with the requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act. After considering public comments, DWR will issue a final EIR and decision on whether to approve the project or alternatives. Doug Obegi at Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) has said the tunnel would worsen the existing threats to native fish, wildlife, thousands of fishing jobs, and farming communities that depend on a healthy environment. He pointed out that both federal and state laws forbid further endangering threatened species by water diversions. Studies and recent history prove that reduced river flow allows salt water to intrude further up the Sacramento-San Joaquin tributaries, impacting water quality taken by local water districts for consumers. For example, the SWRCB approved limited Delta inflow from April to June of 2022 with resulting documented, warming water temperature and salt water intrusions into Delta freshwaters.

On July 27, 2022 the DWR released its Delta Conveyance Project Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR), which is available to the public for comments through Oct. 27, 2022 on its Delta EIR website. DWR is the lead agency which must comply with the requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act. After considering public comments, DWR will issue a final EIR and decision on whether to approve the project or alternatives. Doug Obegi at Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) has said the tunnel would worsen the existing threats to native fish, wildlife, thousands of fishing jobs, and farming communities that depend on a healthy environment. He pointed out that both federal and state laws forbid further endangering threatened species by water diversions. Studies and recent history prove that reduced river flow allows salt water to intrude further up the Sacramento-San Joaquin tributaries, impacting water quality taken by local water districts for consumers. For example, the SWRCB approved limited Delta inflow from April to June of 2022 with resulting documented, warming water temperature and salt water intrusions into Delta freshwaters.

Only a couple of weeks later on Aug 11, Gov. Newsom publicly announced a new $8 billion drought plan detailed in a 16-page document to prepare California for a 10 percent decrease in water supply by 2040. The plan includes a number of conservation and efficiency approaches described in this report, and requests state agencies to create a new Water Resilience Portfolio to bring groundwater basins into balance, restore river systems, increase storage capacities by 4 MAF, expand aquifer recharging, accelerate wastewater treatment and recycling, capture stormwater and invest in desalination while being mindful of coastal ecosystem hazards. He said these changes need to happen on a fast timeline and emphasized that urgent assistance for those with contaminated or drying out wells and low income, rural residents is needed for obtaining clean drinking water. He also appointed former LA Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa as his new infrastructure czar to help obtain federal funding and stimulate the projects.

California State Plans Analysis

The governor’s strategy calls for continuing to move forward with the controversial Delta Conveyance Project. The plan was praised by water agencies but drew criticism from environmental advocates for not addressing agriculture or industrial uses of water and energy aggressively enough. Concurrently, though, five more Delta water agencies signed onto a state, federal and local agreement for a transformational eight-year program to provide substantial new flows in the Bay Delta watershed for recovery of salmon and other native fish, restore wildlife habitat, and provide funding for environmental improvements. Several projects are already underway.

Governor Newsom’s continued plan for another Delta tunnel is a flagrant defiance of state and regional goals, including the legislature, DWR, and SWRCB, to protect and improve the health of delta ecosystems. The speed with which his new conservation plan described above followed the Delta plan unveiling, suggests it was an already developed Plan B, intended to overcome oppositional forces from those concerned about the environment, Delta health and clean water access. The Delta Counties Coalition (DCC) rightly claims that the SWRCB is obligated to protect water supply for the entire state and environment, not just for the water exporters. Tunnel construction would devastate communities in and around the Delta. (Delta Counties Forum: Delta Tunnel Opponents Express their Concerns, Push For Alternatives, July 26, 2022, www.mavensnotebook.com) One might also wonder if the recent plan appeases voters for a politically ambitious governor who barely managed to survive a recall election last year.

The state has repeatedly failed to enforce existing standards to protect fish and wildlife through waivers of standards in order to deliver water to agricultural users. In 2009, the State Legislature passed the Delta Reform Act stating that California policy is to reduce reliance on the Delta in meeting future water needs through strategies of investing in regional supplies, conservation and water use efficiency. Instead, the state is actively pursuing increased exports from the Delta in direct opposition to state law. The reform act created the Delta Stewardship Council (DSC), whose funding was slashed for its Delta Independent Science Board in the fall of 2020 with no public explanation. DSC did not approve the past California WaterFix tunnel project, so is likely viewed as a tunnel opponent.

Under state and federal laws, the SWRCB is required to update the Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan every three years. As noted by SWRCB Chair Esquivel at a Dec 8, 2021 SWRCB meeting, it has been nearly 30 years since the Board significantly updated water quality standards in the Bay-Delta. He stated that the entire watershed needs to be addressed to get at the challenges of ecosystem decline. In 2018, the Board adopted some amendments and flow objectives for the lower San Joaquin River and its tributaries (Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Merced rivers), but those have not been implemented by water agencies as they are voluntary agreements. Chair Esquivel also noted that while the Endangered Species Act is very important, it’s standards are separate from the Bay-Delta Plan standards for watershed recovery. The plan identifies multiple beneficial uses of water, water quality objectives, and reasonable protection of those uses. The objectives are primarily flow dependent. (State Water Board: Bay Delta Water Quality Control Plan Update: Completed and Implemented by 2023?, Dec. 15, 2021, www.mavensnotebook.com)

Conclusion

A recent statewide survey of Californians by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) about what environmental issues Californians are most concerned about revealed that the water shortage and drought (30%), followed by wildland fires (13%), and climate change (11%) are most important to them. Many (68%) did not believe that the state and federal governments were doing enough, nor taking the right actions for protecting them and resolving the issues. Although there were significant political party differences, 59 percent of the respondents still approved of Governor Newsom’s handling of the environment.

In light of Governor Newsom’s proposal, backed by the state’s large water agencies, for the Delta Conveyance Project tunnel and its sister project Sites Reservoir, the public approval of his management policies, in spite of over two thirds of adults believing that not enough is being done, indicates a major deficit of understanding about the scientific causes of the water shortage, the real resources, and what solutions offer the best outcomes. It is also long past time for the tunnel proponents to stop crying wolf and fully disclose information to the public about all the options and numerous costs.

Perhaps the ambivalent survey respondents who approve of Gov. Newsom are ignorant about the about the long-term consequences of ecosystem devastation following the water diversions and subsequent drying of up rivers in the Central Valley and Sierra watersheds. Perhaps they don’t realize that the high costs of tunnel construction will be passed on to them in their water bills, or are unaware of the economic losses as agricultural jobs are lost and food production slows in the Central Valley. Perhaps they are unaware that the tunnel will not produce any new water, unlike wastewater treatment that replenishes the aquifers instead of pumping water back out to the ocean. Perhaps they have not heard or read about the inequities of those with little access to water because the taps and fancy filters in their homes are still plentiful. Perhaps they believe politically biased news that their water supply will not last the year unless urbanites stop all outdoor watering because of low levels in Lake Mead, totally unaware of all the water sources and over-flowing underground water tables in the basements of Los Angeles buildings from a water storage surplus.

Survey respondents are correct, however, that not enough protective actions and good management of water by the state has occurred in spite of science, laws and regulations to do so on both state and federal levels. But to understand why that is true, or how those tunnel and reservoir costs (totaling $40 billion at least, not counting job losses and environmental destruction) are needed for conservation, more Californians need to have basic knowledge about all the sources of water, the infrastructures that deliver water, and who does what. They need to know about sources of pollution for their drinking water too and how it can be alleviated.

Granted, understanding the existing competing and complex labyrinth of all the water, agriculture, food, wildlife, fisheries and environmental organizations, federal and state infrastructures, and the multinational and cultural groups involved with natural resources can be daunting. Most of it is all available on public record and internet, but few people take the time to view and analyze it. Not many people read the linked documents that provide important details of regulations, policies and laws. It is all there, but goes unnoticed by the public until the undesirable consequences play out.

Therefore, this three-part article series offers a shortcut way of learning the water supply and demand basics. And because of the prolonged drought and political claims of dropping levels of river flows and reservoir levels behind dams, major decisions are being made this year (2022) that will determine how our future plays out regarding fresh water in California for a long time to come. Choices will be made between funding the creation of new water supplies through recycling, stormwater capture and increased storage versus continuing to rely on old patterns of just moving dwindling water around to benefit the richest basins. Remember, California is just an example of what is occurring world-wide.

There is a great deal of opposition to the construction of the Delta Conveyance Project, from the state legislature, Delta coalitions, some programs within state government, university fellow scientists, and non-profit watchdog organizations. The USBR will not be providing any funding and federal fish and game departments of the Interior Department, which have a duty to protect the environment. The laws in California also prohibit further destruction of the watersheds. Environmental oriented organizations have been successful in stopping additional Delta tunnels in the past multiple times.

In general, everyone involved with California water shortages agrees that the complexity of institutions controlling the water is one of the most challenging situations. Everyone agrees that there needs to be cooperation. Everyone recognizes that the water rights system is archaic and no longer meets the needs of all residents and industries. Many officials speak or write about the lack of trust between stakeholders, which makes coordination and cooperation difficult when each interest group clings to defense of their own needs. Consumers, too, no longer trust the system. Political shifts can compromise projects since many projects takes years to complete and tend to be interrupted when administrations change. The federal Interior Department has a different perspective than the state, and owns much of the infrastructure because of federal funding. The USBR is demanding that changes in plans be made for the Colorado River water or they will impose their own solutions on the states

Although it is beyond the scope of this series, climate change (climate engineering) and the trending food supply interruptions with loss of farmland must eventually be addressed as important causes of the mess we are facing. Governments around the world have had climate control and free zero-point (Tesla) energy technology for decades that do not contribute to environmental damage. The public would be wise to discern and question the underlying motivations of government in order to keep it on track working for the benefit of the people.

Following the path of money and power usually offers clues to the reality of controlling forces. Basic human needs for clean air and water, actually all the natural resources, should not be taken for granted because humans do exploit those resources. The polluting of Earth in countless ways must stop for our own health. Truth in governance and the media is crucial for our ability to thrive in the very near future and to function as good Earth Stewards. Water is an important element of that future. It’s all about consciousness of the world and reality that we live in.

Please see Part 4 being released tomorrow.

For more on the drought scandal, check out this recent video by Jimmy Dore: https://youtu.be/sAhJak7AiIY

Watch this interview with Elaine and Reinette Senum discuss the issue: https://reinettesenumsfoghornexpress.substack.com/p/citizen-sleuth-elaine-buxton-uncovers?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email#play

And PLEASE circulate this letter from Senator Hurtado who represents the 14th District in California’s Central Valley and contributed to the Clean Water Act. https://sd14.senate.ca.gov/sites/sd14.senate.ca.gov/files/pdf/CA%20Legislature-DOJ%20Water%20Market%20Manipulation%20Letter.pdf

Disclaimer: We at Prepare for Change (PFC) bring you information that is not offered by the mainstream news, and therefore may seem controversial. The opinions, views, statements, and/or information we present are not necessarily promoted, endorsed, espoused, or agreed to by Prepare for Change, its leadership Council, members, those who work with PFC, or those who read its content. However, they are hopefully provocative. Please use discernment! Use logical thinking, your own intuition and your own connection with Source, Spirit and Natural Laws to help you determine what is true and what is not. By sharing information and seeding dialogue, it is our goal to raise consciousness and awareness of higher truths to free us from enslavement of the matrix in this material realm.

EN

EN FR

FR